In the remote Indigenous community of Laramba in the Northern Territory (NT), drinking water contains almost three times the maximum safe level of uranium recommended by the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

On 1 July 2020, the Northern Territory Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NTCAT) found against applicants from Laramba in a case about domestic water provision.

Represented by Australian Lawyers for Remote Aboriginal Rights, residents sought compensation for the domestic provision of contaminated water, as well as filters to improve the safety of their water in the future. NTCAT presiding member Mark O’Reilly found that the landlord – the Department of Local Government, Housing, and Community Development – is not required under the Residential Tenancies Act 1999 (NT) (RTA) to provide safe or adequate water to householders.

The landlord’s obligations under the Residential Tenancy Act were found to apply to physical water infrastructure – domestic pipes, faucets, sinks, and so on – but not to water supply or quality. O’Reilly determined that “the landlord’s obligation for habitability is limited to the premises themselves. It does not extend to external factors that might be considered an ‘act of God’ or a ‘force majeure’.”

One way to understand this failure to provide safe water is as a matter of racial discrimination.

This separation of housing and water issues is typical of legal and policy frameworks, and it highlights the need to consider them together. Housing is permeated by water in deliberate and unpredictable ways. Safe and healthy housing requires the properly constructed entry and exit of water, but water’s presence can just as easily contribute to disrepair and uninhabitability. The need to understand housing as permeable is especially true for the remote communities in central Australia in which government housing construction is being delayed by water security concerns.

One way to understand this failure to provide safe water is as a matter of racial discrimination. Government services in urban Australian contexts rarely contend with the issues seen at Laramba. If urban contexts do face challenges related to drinking water potability, governance and technological solutions are typically put in place.

Section 13 of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) establishes that it is unlawful to refuse or fail to supply goods or services, including supplying on less favourable terms, by reason of race.

It may be difficult to prove in court that substandard government service provision is attributable to the fact that most Laramba residents are Aboriginal, rather than due to the challenges of remote infrastructure provision and the naturally occurring uranium in the water source. However, section 18 offers some promise for the application of the Racial Discrimination Act. It states that where an act is done for two or more reasons, and race is one of those, ‘the act is taken to be done for that reason.’

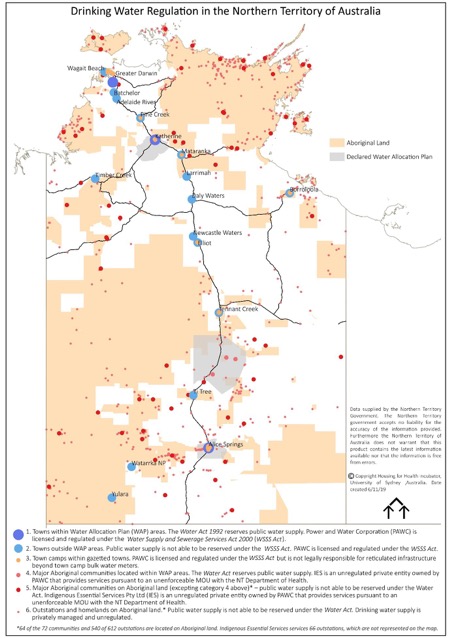

The case for racial discrimination is even stronger if Laramba is considered in the broader context of NT water regulation. Research has shown that protections for safe drinking water vary significantly across NT communities.

In the NT, the Water Supply and Sewerage Services Act 2001 (NT) regulates drinking water. It requires that “water supply services” in “water supply licence areas” are licensed by the NT Utilities Commission. The government-owned Power and Water Corporation (PowerWater) is the current and sole licensee, and is subject to a range of service requirements, including asset management planning, licence compliance reporting, and service planning.

However, the NT has not set minimum standards for water supply, including water quality. Instead, the Department of Health and PowerWater have a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that describes criteria for the safe treatment of water, water testing regimes, responses to public health incidents, public reporting, and so on. Regarding the absence of legal minimum standards, the MOU simply says that the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines “will be used as the peak reference” for water quality. Further, the Water Supply and Sewerage Services Act only applies where water supply licenses exist, namely in the 18 major towns where the vast majority of the NT’s non-Indigenous population lives.

In 72 remote Indigenous communities and 79 outstations, Indigenous Essential Services (IES), a not-for-profit arm of PowerWater, provides water services. In those contexts, drinking water supply is neither licensed or regulated.

To summarise, this means that at Laramba there are no protections against uranium in the drinking water in the Residential Tenancies Act. There are also no minimum standards for water quality under the Water Supply and Sewerage Services Act. IES functions in unlicensed contexts where even the aspirational and unenforceable MOU between the Department of Health and PowerWater does not apply.

This apparent gap between housing and water laws is muddied by the funding and service arrangements that exist between relevant government authorities. IES is funded by the Department of Local Government, Housing and Community Development. IES, in turn, pays PowerWater to deliver water and power services in various remote communities.

This lack of accountability highlights the importance of the recent call by all four NT land councils for the introduction of a Safe Drinking Water Act, to protect drinking water for all NT residents.

The Department, which is the landlord of public housing at Laramba, funds the utility provider responsible for delivering drinking water with high levels of uranium into homes. IES operates without a license and without the protections for water quality that exist in contexts where PowerWater is the licensee. This arrangement should be restated, as it shields the Department and PowerWater from responsibility for failing to provide safe drinking water to households.

The key point here is that in the remote communities serviced by IES, there are no legal protections for safe drinking water. This situation is unequal in its outcomes, and there is potential to explore whether it is discriminatory under law.

It is not an acceptable situation that both the landlord and the utility provider are able to hold at arm’s length the responsibility to supply safe drinking water to remote Indigenous households. It is likely that this separation between housing and water responsibilities will be tested again through appeal.

This lack of accountability highlights the importance of the recent call by all four NT land councils for the introduction of a Safe Drinking Water Act, to protect drinking water for all NT residents.