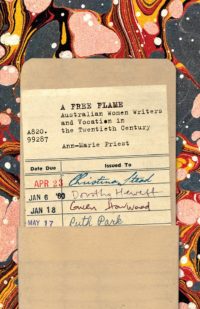

A Free Flame: Australian Women Writers and Vocation in the Twentieth Century

Ann-Marie Priest

When a voice speaks from a burning bush, you do what it says. So I imagine, anyway – I’ve never heard a voice in a burning bush. Ruth Park probably never did either, but it was her way of conveying that her life-long urge to write felt beyond her own control or understanding. It was all she had ever wanted to do. She made sure husband-to-be D’arcy Niland was clear on this point, telling him on the eve of their wedding, “I need to be a writer, that’s what I need from life.”

In A Free Flame: Australian Women Writers and Vocation in the Twentieth Century, author Ann-Marie Priest looks at four notable Australian women writers born in the early part of the Twentieth century – Gwen Harwood, Dorothy Hewett, Christina Stead and Ruth Park. Priest sets out to investigate how much a sense of vocation played a part in their pursuit of writing as a career, in a time when, if women were tolerated in paid work at all, they “were not supposed to seek work that would satisfy or extend themselves; they were supposed to serve others”.

Referencing letters, interviews, biographies, and semi-autobiographical characters from their novels, Priest provides a detailed picture of four women who all felt compelled to write, or knew decisively that they would be a writer, from a young age. In her letters, Stead told a friend, “I had decided when I was six or seven years old that I would be a writer and I never had any other ambition all my life.” Park’s earliest career aspiration was to appear in the children’s pages of the New Zealand Herald. Hewett had “always written poetry, since before I could even write. I used to get my parents up in the middle of the night to write it down.” Harwood set out to be a concert pianist originally, but in letters written as a young working woman, she referred to poems, plays and stories she was constantly writing in her spare time.

Before beginning A Free Flame, I was curious to discover why Priest chose to look at these women through the lens of vocation, and what that focus would add to the body of feminist histories of women artists and writers. A Free Flame frequently reminds us of, but does not dwell on, the systematic barriers women faced in the past, in their attempt to be artists. “For each woman,” says Priest, “every step on the path to living the life of the writer she knew herself to be ushered in a new set of struggles.”

Priest acknowledges other cultural critics who have “pointed out the ways in which the Western ideal of the artist is in direct opposition to the Western Ideal of woman,” naming Virginia Woolf amongst them. I recalled, in A Room Of One’s Own, Woolf describing her anger on being barred from entering a university library because she was a woman. A woman had some nerve, in 1928, expecting to enter such hallowed ground, let alone aspiring to produce the kind of cultural product stored within its hallowed walls!

“Until the last century almost all models of the literary artist were male,” says Priest, reminding us that, until the rewriting of art and literary histories from a feminist perspective began in the 1970s, women were only present in such histories as exceptions to the norm.

“In the early part of the twentieth century, when there was so little evidence that a woman could fill this role and so much hostility towards any attempt by a woman to do so, this was an extraordinarily trangressive thing to claim.”

In light of this, Priest identifies the central question she seeks to answer: “How does a woman come to believe that she is called to a profession – more, an identity – that specifically excludes her?” The answer, she suggests, is the power of vocation to cut through such constraints. A sense of vocation gave these women the determination to pursue writing, despite the personal costs.

Harwood expressed in letters, and in her poems, her feeling that it was selfish, even ‘mad’ to try and carve out time to be an artist. “(I) wish I had never written a line but had stayed making pies in the kitchen. A lot of good savage work gets destroyed in these moods.” Despite international success, Stead continually denied that she was a writer, or insisted that her status was that of an amateur, and preferred, in interviews, to talk about how important love was in her life. Park, perhaps the most well-known and well-loved of all four, came from the poorest background, and approached writing in a business-like way, taking on varied jobs to provide income for her family. She never considered herself a literary writer, but a “working writer” who could “turn her hand to any sort of writing.” Perhaps because of this, she experienced burn out at one point, and Priest notes that “the unspoken and perhaps inadmissible sub-text to (Park’s) autobiography is that despite having devoted herself to writing, she has not been able to live out her vocation.”

A Free Flame is a small but important book for anyone with an interest in literary biographies, Australian literature, or feminist histories. Second-wave feminism gave us the idea, perhaps earth-shattering to some at the time, that the personal is political. In A Free Flame, Priest delves into the personal, to piece together each woman’s private image of herself as a writer. She puts a sharp focus on the internal struggle each woman went through, to reconcile her conflicting identities as a woman and an artist, in a society that attributed vastly different values to those roles. Having a strong sense of vocation did not make the path to literary success – or personal fulfilment – any easier, but that conviction, that urgent need to be a writer, is what kept each woman determinedly travelling along it.