This article is part of our April and May focus on Arts and Human Rights.

By Les Thomas

One of the problems that music and human rights share is that they’re too often seen as optional extras, rather than necessities; especially in a rich country like Australia, where their roles in keeping body and soul together are easily taken for granted. Some see music as a frivolous, disposable consumer product and human rights as an abstract legal concept that has no real bearing on day-to-day life. Alternatively, there are many of us who see them as important as the oxygen we breathe. I don’t think we’re entirely alone, historically.

The First People of this country have used songlines as a way of navigating and connecting to their land and ancestors for millennia. Rhythms and ancestral words and melodies created a map of sound that made countless dangerous journeys possible, supporting and helping to sustain the world’s oldest culture.

Of course, when stripped of freedom, dignity and worldly possessions, the importance of song traditions as a life raft becomes even greater. There’s no missing the fact that American popular music is built on the traditional music of Africa via slavery and Europe via immigration. These were times when people had to sing together to give themselves heart. Their folk (literally “people’s”) music served as a network, an organising tool and an emotional salve against the hardships and injustices of life in the New World. On the surface, the words may be about a better life beyond death, but coded songs like “Wade in the Water” could also instruct on how to escape to freedom.

Wade in the Water, wade in the water children.

Wade in the Water. God’s gonna trouble the water.

Escaping slaves could walk in streams to throw the slave owners’s hounds off their trail.

So how does any of this relate to present-day Australia? In my own experience organising These Machines Cut Razor Wire concerts to support the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, I’ve been very pleasantly surprised at how easy it is to find wonderful, compassionate musicians to perform. Politicians tell us that the general public don’t like asylum seekers and they’ve routinely exploited them to win votes since 2001. But if people are hostile, why are so many musicians willing to help?

My best guess is that we are in the job of empathising and walking in other people’s shoes a lot of the time. How can you sing the blues without thinking about the crucible of suffering it was born out of? You might be singing a love song with nothing to do with the state of the world, but you’re still sharing an emotion. While there aren’t too many people accustomed to getting up on a soapbox these days, they can apply their music to a cause they believe in, explicitly stated or not.

The best example I know of a musical statement where words weren’t necessary is that of Vedran Smailović, a cellist from Sarajevo. In 1992 when his city was under siege, his response was to set up his chair within the craters of bombed-out buildings and perform pieces like Albinoni‘s “Adagio in G Minor” once through for each person killed there.He showed remarkable fearlessness in making plain that the culture of his city could not be killed. The contrast between his shared creativity and vulnerability against the cruelty and destruction of war couldn’t have been starker. In that time and place, the notes resonating from his strings spoke a message of hope and healing that words were insufficient for.

Given the present situation in Australia, I feel that words are very necessary on many fronts, including defending human rights, so when Trevor Grant asked me to write a song based on a letter from an asylum seeker named Selva who’d been detained for 37 months, I felt well primed to do so. Using as many words from the original letter as possible and a simple chord progression in the people’s key of G, I wrote “Song for Selva”. One week later I was recording the song with Jeff Lang in his Enclave Recording Facility. Apart from being an incredible musician and producer, Jeff’s shared commitment and directness in dealing with the subject made it easy. By 4:30pm we were listening to a fully tracked and mixed song which was mastered by lunchtime the next day by Adam Dempsey.

Trevor and I were able to pass on a disc to Selva himself during a visit to the Broadmeadows Detention Centre a few days later. Just outside our meeting room a group of 27 ASIO detainees were on hunger strike, with one being taken to hospital that afternoon. Management had drawn the blinds to make them less visible. Watching and listening to Selva, a young, gentle man with a lot to offer, it was impossible not to think about the sheer waste and needless suffering in detaining people like him.

I asked if there were any musical instruments there and he said, “Yes, but people are too far gone to play them.” Over the next few days I received word that detainees were playing the song loudly inside the centre to boost morale. Melbourne community radio stations like 3RRR, 3PBS and 3CR were also showing great support.

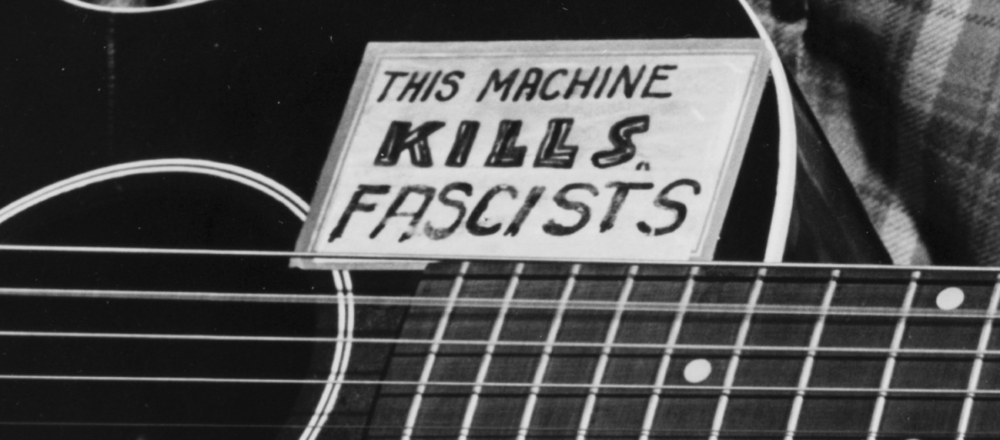

On the Thursday of the following week, friends from The Eastern, an excellent New Zealand band, asked me to pop down to their gig at The Yarra Hotel to let people know about These Machines. Mick Thomas (of Weddings Parties Anything) has recently refurbished The Yarra. In a chat later on, Mick commented on the way Hillsong Church use the power of music to inspire their people in a way that political progressives don’t. It’s painfully true. Whereas once balladeers like Woody Guthrie and his predecessors had no hesitation about describing matters personal and political, a lot of musicians now tend to avoid contentious topics for fear of offending, losing gigs or not appearing well enough informed. When making any kind of living out of playing music is such a challenge, it’s not hard to see why most players would be inclined to leave activism out of their setlist.

I arrived home from that gig with a direct message from Selva himself saying that after 37 months, he would be released the following morning into community detention. His case is still not finalised, but it’s a wonderful, positive development that his supporters believe the song helped to deliver. It’s impossible to say that for certain, but clearly the timing is extraordinary and it shows that scrutiny and attention to cases like that are necessary.

When a songwriter sits down with an instrument and a notepad to create a song of protest, there is usually a strong compulsion behind it, events larger than the individual that they feel need addressing. In that way “Strange Fruit” by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish high school teacher from the Bronx, directly confronted racist lynchings of Black people in the USA’s southern states and the racism that made it possible. At the first performance of that song, by Billy Holliday at New York’s Society Café in 1939, its potency was clear – from the total silence that followed, and then the near panic of some in the audience.

In his own words, Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changing” was a very deliberate attempt to write a “big song” which related to the folk music and civil rights movements. Part of the wonder about a song like that is how it can take on lives of its own, being sung by thousands of people in the service of hundreds of different causes.

Another extraordinary song, Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody’s “From Little Things Big Things Grow” has probably done more for the popular understanding of modern Indigenous history than any book. It uses direct words, an unforgettable melody and a simple revolving chord progression so that even the youngest school kids all over the country can know who Vincent Lingiari was and why what he did was important.

Examples like this give me no doubt about the close relationship between music and human rights. That’s why it makes sense to me that we use it to its full advantage to help bring us together, highlight injustices, share knowledge, lighten our load and, ultimately, set us free.

Les Thomas is a singer/songwriter, editor of Unpaved and founder of These Machines Cut Razor Wire.