Hundreds of thousands of people have taken to the streets around the world in protests triggered by the brutal death of black American man George Floyd. This worldwide movement for anti-racism is magnified at home in Australia where First Nations people are subjected to discriminatory laws and racist policing that have cost 437 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people their lives in custody.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the most incarcerated people in the world. This is a result of both discriminatory policies and discriminatory policing.

This weekend, as many of us joined protests and rallies around the country, an updated death toll was announced, putting Aboriginal deaths in custody at 437 since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was held in 1991 – the Royal Commission that was meant to end blak deaths in police and prison cells.

In Australia, we need to end the mass incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and cut the disproportionate burden of family violence that is borne by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly women and children. Change the Record is Australia’s only national, Aboriginal-led justice coalition campaigning to end this injustice.

A week before George Floyd’s death sparked global protests, Change the Record released Australia’s only national inquiry into the impact of Covid-19 policies on First Nations communities around the country – ‘Critical Condition’.

The report is the culmination of expert testimonials and evidence from frontline Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services, Family Violence Prevention Legal Services, community legal centres and human rights organisations around the country who have been directly impacted by Covid-19 regulations and policy restrictions.

Critical Condition is a real-time examination of the many damaging and punitive impacts of Covid-19 policies on First Nations people. It examines the impact of Covid-19 policies on: Policing, Prisons, Family safety, and Children in out-of-home-care; and provides recommendations to government for the coming weeks and months as Covid-19 restrictions undoubtedly continue in some form.

Policing

Over-policing, police brutality and the mass-incarceration of black people has suddenly dominated news headlines in Australia after the death of George Floyd in the US. The fact is, we don’t need to look to America to see the impact of discriminatory and heavy-handed policing on First Nations people. Just last week, video footage captured a young Aboriginal boy being slammed to the ground by an armed police officer.

There has been considerable discussion in the community about the role of police in enforcing Public Health guidelines – particularly as some sections of the community have interactions with police for the first time. Critical Condition found that while First Nations people came into contact with police at disproportionate rates prior to Covid-19, this has continued during the pandemic with reports of disproportionate numbers of infringements being issued in areas with high Indigenous populations – and concerning reports about heavy-handed policing in regional areas.

The fact is, we don’t need to look to America to see the impact of discriminatory and heavy-handed policing on First Nations people.

For example, almost one third of all infringement notices issues in the Northern Territory were issued in the small, regional town of Tennant Creek. Tennant Creek has a population of 3000 people, about fifty percent of whom are Aboriginal. The residents of Tennant Creek reported police attending their homes and requiring residents to stand for headcounts; going to houses that were known to authorities as overcrowded and demanding residents leave; and entering homes citing public health guidelines and tipping out alcohol. Amnesty’s International Indigenous Advisor said that this was “one of the only times in my career that I have had families too scared to speak up.”

The residents of Tennant Creek reported police attending their homes and requiring residents to stand for headcounts.

Prisons

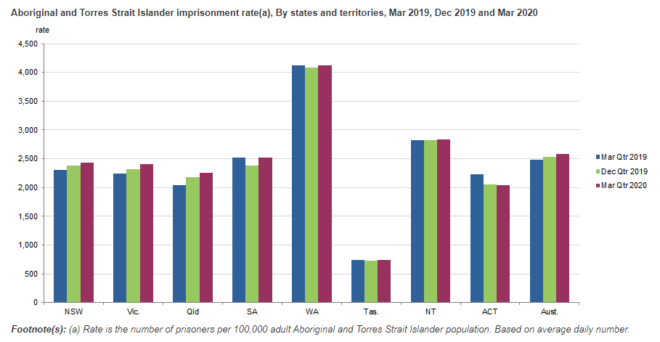

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody released almost three decades ago said that to stop Aboriginal deaths in custody we must stop putting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prison. Australian Bureau of Statistics data released last week show that we are doing the opposite.

The ABS statistics show that the daily average number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prison increased this quarter by 5% compared to the December and March quarters last year.

This is the moving in the wrong direction – particularly during a pandemic.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prisons are at particular risk if there were to be a Covid-19 outbreak. First Nations people have higher rates of chronic illness, disability and respiratory complications than the broader population due to the far-reaching consequences of colonisation, trauma and persistent socio-economic disadvantage — and prisons present a particular risk for disease transmission because they are overcrowded, often unhygienic closed environments.

The daily average number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prison increased this quarter by 5% compared to the December and March quarters last year.

They are also high-risk environments for human rights abuses. Critical Condition looks at some of the measures put in place by correctional facilities in an attempt to reduce the risk of Covid-19 spreading which, in turn, have harmful impacts on the freedoms and human rights of people in prison.

The report documents people in prisons being denied soap, having to spend their own money to make phone calls to their families after visits were banned, and being denied confidential legal visits. This means once again Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are spending longer periods in prison in potentially dangerous conditions.

Family safety

International evidence clearly documents that during disasters family violence often increases and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – particularly women and their children – are disproportionately affected in crises such as Covid-19. This is borne out in the evidence in Critical Condition.

The family violence prevention sector is already underfunded and under-resourced. During Covid-19, these limited resources were placed under even greater strain. The Family Violence Prevention Legal Service reported women being turned away from women’s shelters, police being unable to assist in crises and barriers to accessing courts for legal protections.

One case study that typifies the challenges faced by Aboriginal women and their families, was the story of Regina in the Northern Territory. She was assaulted by her partner and sought legal assistance. Lawyers tried to assist Regina to access the Women’s Safety House but in this community the Safety House is run by police, and the police advised that they were unable to assist as their resources were required on border and checkpoint patrols.

Children

The stories in Critical Condition confirm what numerous reports have found before – that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are still being taken from their families and communities at far higher rates than the rest of the population. This is devastating for these kids, for their families and for the whole community.

The Covid-19 pandemic has put enormous stress on everyone, but for Aboriginal families the burden is even greater. Critical Condition documents the stories of babies being removed at birth and families having to fight to see photographs, mothers being denied visits with their young children and the fear that this will impact on their future ability to be reunited as a family.

We heard one story of a mother in Tasmania who reported that the Child Safety Service had refused to facilitate face-to-face visits with her child. So, she went from face-to-face visits every week before the pandemic, to just one weekly phone call with her child. This has been extremely distressing for her. What’s more concerning is that Child Safety has been unable to give mothers and their lawyers clear advice about whether this loss of regular contact will threaten their prospects of reunification as a family.

One story of a mother in Tasmania who … went from face-to-face visits every week before the pandemic, to just one weekly phone call with her child.

What now?

Right now, we face a critical turning point.

Hundreds of thousands of people have called for change. We have decades of evidence that spells out what governments must do to save blak lives. As the spread of Covid-19 slows in Australia and businesses, the economy and public places gradually re-open, we have to reconsider the Covid-19 policy measures implemented so far – what’s working, what’s not working and what should continue into the future.

There is little doubt that there will be future outbreaks of Covid-19 in Australia and that communities will continue to be affected by Covid-19 policies and restrictions in various forms. Critical Condition highlights the experiences of First Nations communities to decision-makers and makes ten key recommendations to ensure the human rights, health and safety of First Nations people are protected. Read them here and join our movement for justice and equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.