This article is part of our February theme, which focuses on one of the great silences in the human rights conversation in Australia: Prisoners’ Rights. Read our Editorial for more on this theme.

In September 2009 the Queensland Government passed amendments to the Corrective Services Act 2006 relating to the selling or exhibiting of prisoner art whilst the artist is in custody. The legislation defines prisoner artwork as visual art, performing art or literature produced by a prisoner. Ostensibly intended to protect victims of crime, the amendments instead only hamper efforts at rehabilitation and further punish those whose liberty we have already taken away.

The changes prohibit prisoners from selling or have somebody sell on their behalf their artwork whilst they are in custody. Artwork is allowed to be gifted but only with the permission of the prison’s general manager. They can consider a wide range of factors such as “the value of the work” and the number of “gifts (the artist has) made in the past.” Artwork is also allowed to be passed on to a third party for safekeeping if the artist has been given permission to do so. The person holding work for safekeeping is not allowed to sell it, exhibit it in a gallery or give to another person. If they do so they have committed an offence.

The legislation does not specifically limit the amount of artwork a prisoner is allowed to produce. However, as prisoners have a limited amount of space for personal property, unless they are given permission to have their work stored by another person (supposing they have someone willing to do so), they are forced to dispose of most of their work.

There is a growing, global understanding of the benefits art has for rehabilitation in prisons.

Officially the government has stated these laws were designed to protect the victims of crime from having their experience exploited in the search for fame or profit. It is not clear however, what incident set the precedent for such changes, as there appear to be no cases in Queensland of a prisoner becoming famous through artwork about their crimes. The danger is that if Corrective Services maintains control over what works can and cannot leave the prison grounds then they can effectively silence the voice of those inside and open the door to censorship.

In contrast to these amendments, there is a growing, global understanding of the benefits art has for rehabilitation in prisons. Working to produce something of value can increase a prisoner’s sense of self-esteem and be a powerful therapeutic tool for those who distrust oral communication. This year, the Koestler Trust, a charity in the UK, is celebrating its 50th year of promoting and awarding arts in prisons. Their philosophy is that prisoner art benefits both the individual and the wider community to “channel offenders’ energies to positive ends, to build their self-worth and help them learn new skills.” On their website they tell the story of Peter Cameron, who entered jail as a drug smuggler and came out an artist.

Working to produce something of value can increase a prisoner’s sense of self-esteem and be a powerful therapeutic tool for those who distrust oral communication.

Matilda Alexander, the coordinator and principal solicitor of Prisoners’ Legal Service (PLS) in Queensland, believes these laws constitute a violation of the prisoners’ human rights. In the past, PLS has held art auctions that provided prisoners with the opportunity to display their achievements. The auctions also raised much needed funds for PLS to fly lawyers to remote locations in far north Queensland where there is great need for the services they offer. To run such a show, they would need permission from Corrective Services. They have however been told that theirs is exactly the sort of exhibition the laws were designed to prevent. Alexander says PLS would be concerned about running a show where Corrective Services had artistic control and the ability to censor unflattering works.

Prisoners have voiced their frustrations to PLS about these amendments and the limitations they place on their creative expression. For many of the Indigenous people in prison art provides a direct link to their culture. In this sense the new laws come into conflict with the World Health Organisation’s acknowledgement that access to culture is a human right.

Art is a non-violent form of self-expression, personal development and therapy.

Art is a non-violent form of self-expression, personal development and therapy. The opportunities it gives an individual to improve and change their lives are immeasurable. The fact that a state in a country like Australia would choose to deny this to those in their care is simultaneously bizarre and irresponsible. It goes against all progress made in the effort towards rehabilitation and decreasing the chances of reoffending. Unfortunately prisoners’ art is not a subject many Australians take the time to discuss. Yet the censorship of creativity and culture, and the abuse of authority, is relevant to all of us. So it is time we had this conversation and reminded ourselves that it is often the small amendments that have the biggest impacts on people’s lives.

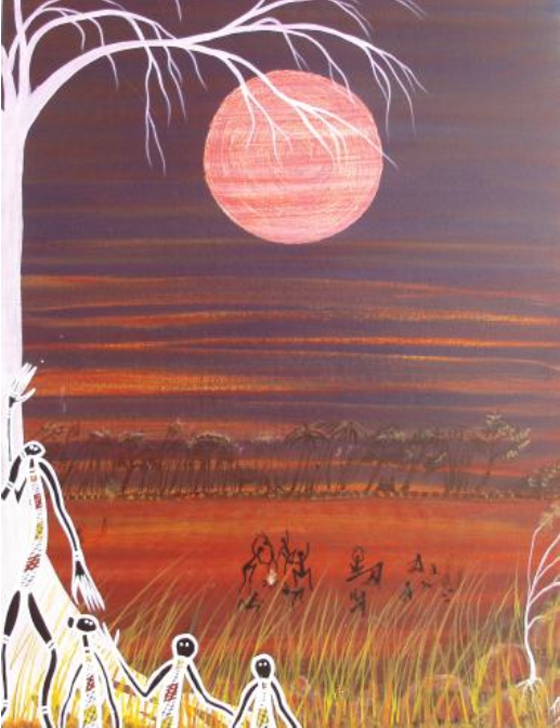

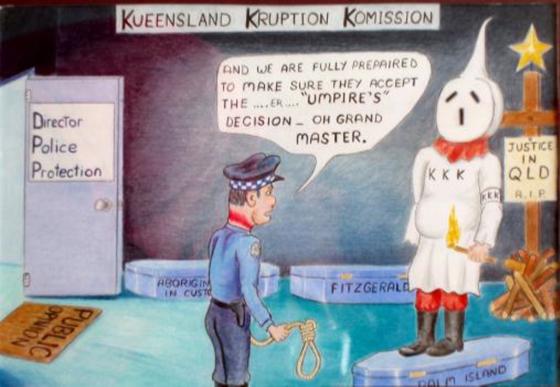

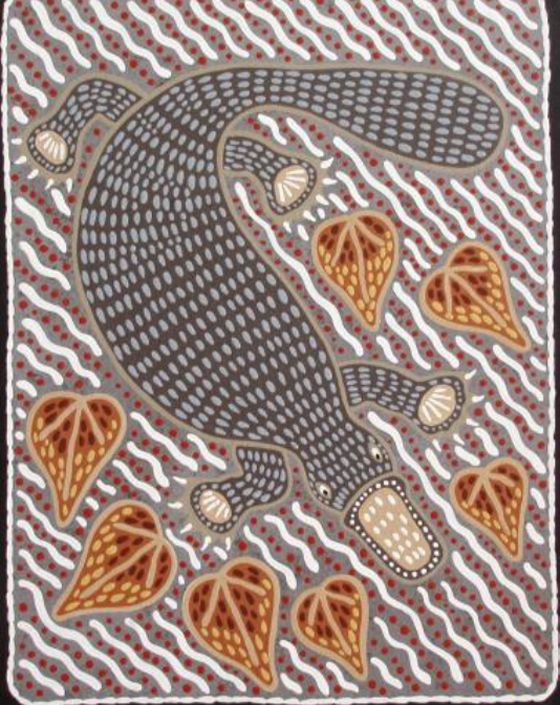

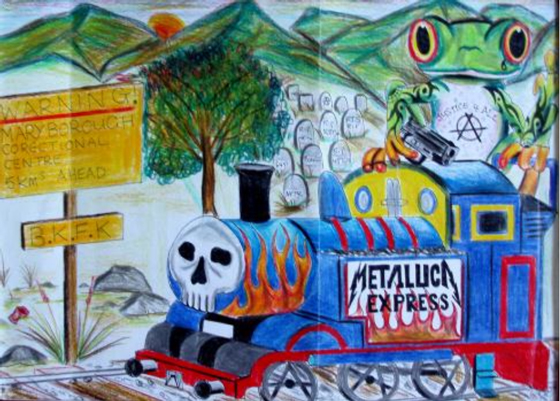

The following artworks were provided by the Prisoners’ Legal Service and are featured here with the kind permission of the artists.

Tim Hardy, Activities in Moon Dance (76 X 51) Medium: Acrylic on board

Steve Stewart, Image of Goanna (36 X 21) Medium: Colour pencil on paper

Tim Hardy, Image of Crocodile (51.5 X 33) Medium: acrylic on paper

Steve Stewart, Image of Kueensland Kruption Komission (19 X 27) Medium: Colour pencil on paper

Charlie Issacs/Mr Mudjille Mime, Image of Platter puss (35.5 X 45.7) Medium: Acrylic on board

D. Boucher, Breaming Image 2 (76×51), Medium: Acrylic on board

Stuart Palmer, Metallica Express (32X29.5) Medium: Colour pencil on paper

Tim Hardy, Image of Goanna (39 X51) – Medium: Acrylic on board

Tim Hardy, Crocodile (76 X 51) Medium: Acrylic on board