THE SHADOW KING

By Evelyn Tadros

A modern reinterpretation of any Shakespearean play is fraught with danger. Done badly, the adaptation can feel jarring, the parallels laboured and the pompous affectation of Shakespearean English completely out of place. But co-creators of The Shadow King, Michael Kantor and Tom E. Lewis, wisely unshackle themselves from the confines of the 400-year-old script and take only what they need to create a quintessentially Australian drama about two Indigenous families torn apart by jealousy, greed and revenge.

Drawing natural and surprisingly pertinent parallels between the tragic myth of King Lear and modern-day Indigenous disputes over land and mining royalties, The Shadow King is Australian theatre at its finest.

By giving the cast the freedom to rework Shakespeare’s script and translate it into their own dialect … the characters [become] even more complex and nuanced than those in the original.

Translating Elizabethan English into a fusion of Australian English, Kriol, Yolngu Matha and other Indigenous languages not only brings authenticity to the story and characters, it also does what many other modern adaptations of Shakespeare fail to do – it connects. The brilliance of The Shadow King lies in the multidimensional way it is able to connect with audiences.

By giving the cast the freedom to rework Shakespeare’s script and translate it into their own dialect, the play becomes all the more familiar and personal, and the characters even more complex and nuanced than those in the original. With the realisation that what is happening on stage is happening in real life, right now, right here in Australia, suddenly the myth transcends into reality and the tragedy really hits home.

Although deeply affecting, there are humourous moments throughout the play, which will charm and endear audiences. These come largely via the standout performances of Tom E Lewis as Lear and Jimi Bani as the bastard child, Edmund.

With Bart Willoughby and his band playing a mixture of reggae-infused rock, traditional Indigenous songs and dramatic soundscapes live on stage, it is difficult to not be enthralled by the play. All the more so, with the ingenious and cleverly crafted set, which literally leaves the audience, at the most opportune moments, feeling like deer in headlights.

When Right Now Radio spoke to Tom E Lewis recently, his jubilation about sharing Indigenous stories, language, dance and music was palpable. It is easy to see why. After leaving this play, one can’t help but feel a sense of having seen something uniquely special; something that will be talked about, written about and memorialised in the history of Australian theatre for years to come. The Shadow King is a must-see show at the Melbourne Festival.

The Shadow King is showing from 11 to 27 October at the Malthouse Theatre as part of the Melbourne Festival.

Evelyn Tadros has been selected by Multicultural Arts Victoria to be a cultural ambassador for Melbourne Festival.

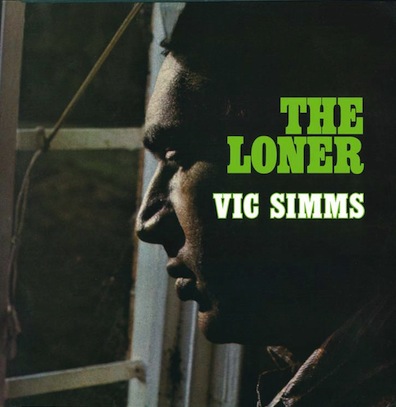

‘THE LONER’ – VIC SIMMS

By Imogen White

Vic Simms’ The Loner was recorded in 1973 during one swift hour at Bathurst Jail, where Simms was midway through a seven year term for robbery.

As a musician who can, in his own words, “tread the boards with any kind of music and play to any kind of audience“, Simms created a collection of appealing and direct songs that focus on the nature of the injustices that impacted upon and surrounded him as a young Aboriginal man in an overwhelmingly white Australia. He traded cigarettes for an acoustic guitar, penned a series of songs about his life before incarceration, and somehow – thanks to a distinctly fortunate series of right-place-right-time events – ended up recording these songs in the very place that was a setting for the kind of oppression he wrote about.

The protest songs that fill his 1973 album – The Loner – should have been melodically and powerfully ringing in the ears of Australians for the past four decades.

Simms is a stage veteran. At age 11, whilst singing ‘Tutti-Frutti’ at a surf club, he was heard by Col Joyce and the Joy Boys who, impressed by his talent, took him on tour with their entourage. He shared the stage with stars like Johnny O’ Keefe and released his first single for Festival Records at age 15. Once imprisoned, this musical past of his re-emerged and he was heard singing in the desolate yard of the jail by a visiting charity group, who decided to take a tape of his music to RCA Records. RCA then came to the jail armed with a mobile studio and recorded his ten songs in a speedy yet sharp recording session that seemed almost miraculous, given the overwhelming inhumanity of the jail in which it was taking place.

Bathurst Jail truly was a hell hole. Windows without panes of glass left prisoners mercilessly exposed to the ferocity of unpredictable weather. Nature became an additional weapon in the cavalcade of draconian measures that were deployed to punish prisoners. As Simms himself said in an interview with Mess and Noise’s Aaron Cullen, ‘The rain and sleet blew straight into the cells. They’d only give you one thin jumper and if you were caught trying to get another jumper you’d earn six additional days in solitary. You’d get solitary for 24 hours or even 48 hours for just having a button undone. The rules and regulations were so restrictive, like colonial times. You had to keep on your feet all day; you weren’t allowed to sit down.”

Inspired by the likes of Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, Simm’s music is a powerful and important testament to the strength of the human spirit in the face of oppression and hardship. Although the recording of the album took place as a PR exercise enacted by the prison to distract the public from the bad press that its inmates’ riotous protests against the atrocious living conditions had generated, the album now finally has the chance to stand clear of this co-option. After a forty year hiatus – where the only way you could hear Simms’ album was to trek to the national Film and Sound Archive – The Loner now emerges triumphantly, able to speak clearly and profoundly of the injustices that Simms, along with many others, faced as young Indigenous people in Australia in the seventies.

Vic Simms should be a household name. I should have known who he was, years rather than hours, before deciding to start writing this piece. The protest songs that fill his 1973 album – The Loner – should have been melodically and powerfully ringing in the ears of Australians for the past four decades. This year’s re-release of The Loner by Sandman Records may bring Simms the recognition he rightfully deserves.

With 2013 marking Simms’ fifty seventh year working in the music industry, the re-release of this album is powerful proof that his voice will not be silenced. As Simms says, “If I didn’t record that album, it would just prove that we were out of sight and out of mind. I wanted to show that musical talent could exist no matter where it was, out in the bus or behind walls.”