By Sonia Nair

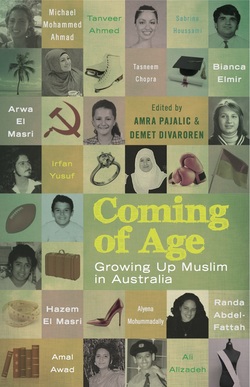

Coming of Age: Growing Up Muslim in Australia | Edited by Amra Pajalic & Deme Divaroren | Allen & Unwin

A book entitled Growing up Christian in Australia or Growing up Buddhist in Australia would be somewhat redundant. No religious group in Australia has been subject to the level of discrimination, harmful stereotypes and outright vilification that Muslims have.

The 2005 Cronulla riots, hysteria engendered by both shock jocks and columnists in the aftermath of September 11, and incidents such as racist comments from the current Prime Minister and a parliamentary inquiry stating it is “overwhelmed by concern about Islamic integration” have coalesced to thrust Islam – and subsequently Muslim Australians – into a spotlight that had hitherto been occupied by a group as severely misunderstood.

Coming of Age: Growing Up Muslim in Australia (curated and edited by author and teacher Amra Pajalic and writer and editor Demet Divaroren) is a bildungsroman of sorts, focusing on the moral and psychological coming-of-age experiences of its many contributors as they transition from youth into adulthood. More than that however, the book lends a platform to voices often marginalised by mainstream media and paints the diverse experiences of Muslim Australians – commonly misconstrued to be one dominant group – who originate from more than 70 countries.

Coupled with the typical pains of teenagehood – infatuations, heartbreak, peer pressure and body image issues – the many accounts run through the added challenges of manoeuvring a Muslim identity often thought to be incongruous with Australian Anglo-Saxon customs, and the expectations of strict parents that manifest in the form of curfews, friendship limitations and cultural commitments.

Some of the anthology’s contributors may be familiar to readers, such as: director of Western Sydney literacy movement Sweatshop, Michael Mohammed Ahmad; regular Daily Life and The Vine columnist, Amal Awad; and poet, novelist and critic, Ali Alizadeh. Ahmad kickstarts the collection with an engaging piece that jumps from how he struggled with being an Alawite Muslim in a predominantly Sunni community to his decision to eschew cigarettes, drinks and alcohol at a pivotal time in his life.

“… I decided I wanted to wear the veil. It was a personal decision – a mixture of faith, identity, self-determination …”

Alizadeh’s account is of an altogether different kind as he details his rejection of religion at the age of ten. Although Alizadesh’s parents decision to migrate from Iran to Australia inadvertently saved him from a country where you could be prosecuted for being an atheist, Alizadeh’s non-belief in God did not stop him from being “rebranded as a Muslim” in the aftermath of September 11.

He recounts:

“I found it difficult that people now saw me as kin to the diabolical killers who fly passenger planes into buildings and slaughter civilians in nightclubs and airports, the bloodthirsty fanatics who preach anti-Semitism and homophobia, the psychopaths who stone women and strap explosives around children.”

Alizadeh’s experience taps into the embodiment idea of white privilege: a terrorist that turns out to be white is viewed as the exception rather than the rule.

Awad’s more light-hearted piece is another highlight, as she ruminates on the familiar age-old conundrum of finding a life partner. For Awad however, this process takes place in her living room under strict parental supervision.

“It’s what we jokingly call the ‘five-minute engagement’. One of the fathers or male elders reads the opening verse of the Quran to signify an intention of courtship, but you can’t do any of the intimate stuff that a couple would do until you’ve tied the knot with an Islamic contract.”

Incongruous as Muslim faith is to a number of Australian customs, many Muslims successfully merge the two on a daily basis. Bianca Emir and Hazem El Masri detail how they turned to sport – kickboxing and football respectively – to negotiate their sense of identity and wellbeing while being caught between two worlds. Both have successfully maintained their Islamic faith alongside their love for contact sports.

Meanwhile, Randa Abdel-Fattah’s searingly honest and funny account of the body image issues she encountered in her teenagehood sheds some light on why Muslim girls decide to don the hijab, and why it is neither synonymous with a sexist construct that objectifies women as certain Western feminists make it out to be, nor a decision they are goaded into taking.

Abdel-Fattah says:

“Towards the end of Year 7, I decided I wanted to wear the veil. It was a personal decision – a mixture of faith, identity, self-determination – and I made it without consulting a single person. It came as a surprise to my family.”

Being a Muslim in Australia is wrought with its own challenges, but Alyena Mohummadally’s account is especially crucial to the diverse framework of voices found in Coming of Age, as she talks frankly about how she came out as a Muslim lesbian.

Coming of Age is an invaluable insight into the varied experiences of Muslim Australians that debunks stereotypes and explores the multifaceted aspects of juggling a hybrid identity. The book’s message is all but cemented as one reaches the final pages – there is no one experience of being a Muslim in Australia.

Coming of Age: Growing Up Muslim in Australia is published by Allen & Unwin