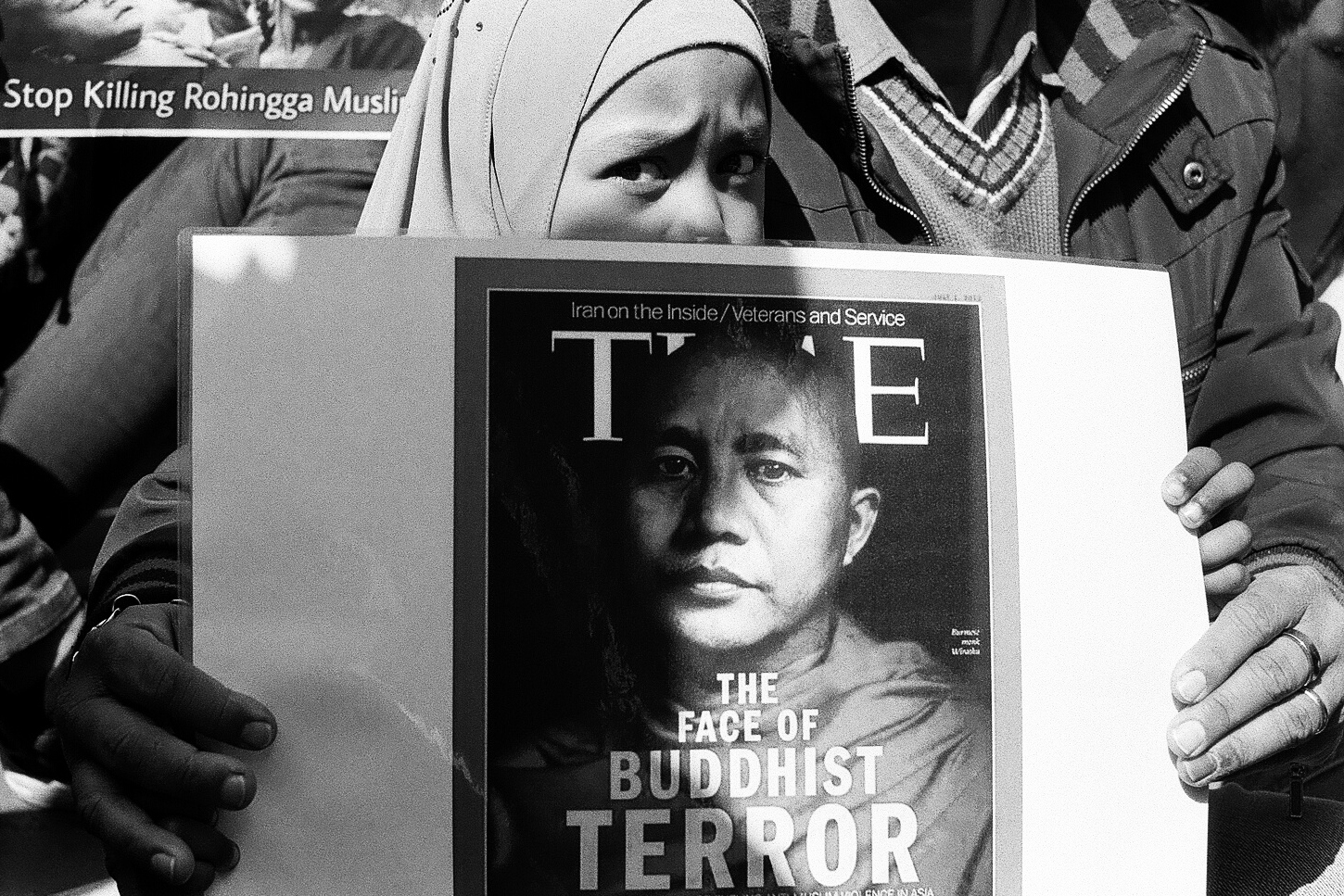

Recently, protesters converged on the State Library of Victoria to make their voice heard in response to the escalating Rohingya crisis. For the mostly Muslim cohort, it was a voice of frustration, anger and desperate hope; understandably so, as what hope is being extended to their Rohingyan compatriots?

The Rohingya are famously described in humanitarian parlance as the ‘world’s most persecuted people’; current events would prove nothing less. A stateless people without citizenship rights in any nation, they are now besieged by the Myanmar Army intent on driving them out of the country.

The stories emerging are shocking: beheadings, the rape of young girls, villages burnt to the ground, and most recently, the use of land mines against civilians.

Rohingya vigil. Photo: Ali MC

Meanwhile, thousands of words have been devoted to decrying the silence of Myanmar’s default democratic leader Aung San Suu Kyi. Calls have even been made for her to hand back her Nobel Peace Prize.

Yet, this belies a deeper misunderstanding of the current crisis, and Australia’s involvement in it.

Recently, I held an exhibition of medium format photographs that I shot while visiting Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) and refugee camps, in both Myanmar and Bangladesh. In the exhibition text, I described Myanmar’s “militant Buddhists” – the phrase confused many people.

The term ‘Bengali’ reflects the general opinion in Myanmar that the Rohingya are simply Bangladeshi illegal migrants. This, despite the Rohingya having been settled in western Myanmar for around 400 years.

The West does not normally think of Buddhists as “militant” – yet there is currently a politically influential and powerfully vocal anti-Muslim Buddhist sect called the 969 movement operating in Myanmar.

As was found in the recent Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, anti-Muslim sentiment runs deep in the country, and attacks have been directed towards other Muslim communities – most notably in the 2013 massacre in Meiktila.

The conflict between Buddhist and Muslim has been simmering for decades, with notable escalations in 1978 and the early 1990s causing Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh and elsewhere.

In 2012, an attack on Buddhists in Rakhine State led to the Muslim quarter in the Rakhine capital Sittwe to be burned down, and around 140,000 Rohingya interned in IDP camps and deprived of freedom of movement, education and medical aid.

In Myanmar, the word ‘Rohingya’ is not even spoken. ‘You mean the Bengali camps,’ the Army officer issuing my permission to visit the IDP camps informed me.

The term ‘Bengali’ reflects the general opinion in Myanmar that the Rohingya are simply Bangladeshi illegal migrants. This, despite the Rohingya having been settled in western Myanmar for around 400 years.

Whether Aung San Suu Kyi is herself a militant Buddhist remains to be seen. Her silence has certainly angered the international community, especially those humanitarian advocates who invested so much in her cause while she was the victim of human rights abuses.

The silence of Aung San Suu Kyi can be heard as a callous indifference to the Rohingya crisis. It can be heard as a betrayal of human rights.

Protesters’ signs at the Rohingya vigil. Photo: Ali MC

Yet, it can also be heard as another tragic misunderstanding of localised context.

As has been the case in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and numerous other interventionist excursions, local politics continues to dominate the West’s best intentions, including the brutal crackdown on Rohingya as Myanmar transitions into some kind of democracy.

Myanmar – formally known as Burma – is comprised of a number of religiously diverse ethnic groups. The country itself was only formalised after the collapse of British India in 1948, after which such groups suddenly found themselves part of this newly formed, independent state.

Since that time, ethnic wars have played out between the Kachin, Karen, and other peoples, in some of the longest-running conflicts in recent times. Further complicating matters in Rakhine State is the conflict between the separatist Arakan Army and the Myanmar Government, which has itself resulted in an increase in Internally Displaced Persons.

The term ‘Burma’ came from the dominant ethnic group ‘Bamar’, whom the British had originally granted power in the form of indirect colonial rule. This Buddhist majority held sway after independence by way of the military junta, and continues in the current governmental arrangement; it is no secret that Aung San Suu Kyi is also a Buddhist Bamar.

The silence of our own ambassadors almost matches that of Aung San Suu Kyi, with foreign Minister Julie Bishop calling for ‘both side’ to show ‘restraint’; soft words indeed in the face of ethnic cleansing, and a disingenuous statement that assumes there is some kind of power balance in the conflict.

Not only are Aung San Suu Kyi’s politics informed by her ethnic and religious background, but also by the newly formed Myanmar power-sharing constitution. The slow transition to democracy has meant that Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy only has control over half of the government portfolio. The other half – which includes the Army – is still run by the military.

Neither of this, however, excuses Aung San Suu Kyi’s silence; but it goes some ways to explain a localised context, which the West is only beginning to understand. In response, a petition has been generated which calls for an arms embargo against Myanmar, with General Min Aung Hlaing being cited as ordering the attacks against Rohingya.

And what about the West’s complicity?

Australia currently gives Myanmar between $60–70 million in aid, in part to promote ‘peace and stability’ in Rakhine State, where the Rohingya crisis is currently playing out. In 2014, the Australian Army began training with the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar Army. The silence of our own ambassadors almost matches that of Aung San Suu Kyi, with foreign Minister Julie Bishop calling for ‘both side’ to show ‘restraint’; soft words indeed in the face of ethnic cleansing, and a disingenuous statement that assumes there is some kind of power balance in the conflict.

It comes as no surprise that there are gas deposits in and around Rakhine State, which also happens to be the second poorest region in Myanmar.

As Myanmar has ‘opened up’ in its transition to democracy, so have the business opportunities, for example, a new oil pipeline that runs directly from Rakhine State to Yunnan province in China that has recently opened.

The Rohingya crisis presents another, even more important opportunity for Australia, and that is to demonstrate to the Muslim community – both in Australia, and overseas – that we are sympathetic to all refugees (not just Christian ones), and we are serious about resolving religious tensions in the region in a variety of capacities.

Signs pleading the public to take notice of the human rights violations suffered by the Rohingya. Photo: Ali MC

The Australian government recently committed to financing and contributing arms to the Philippines’ despotic president – who is currently waging a ‘drug war’ against his own citizens – in order to quell Islamic threats in the south. The flip side of a questionable militaristic policy would be to take in Rohingya refugees, to demonstrate Australia is also a friend to Muslim people.

At Saturday’s protest, Greens leader Richard Di Natale called on the Australian government to commit to a refugee intake quota similar to that during the height of the Syrian civil war. This is not an unrealistic, or unreasonable, demand.

Perhaps the sticking point for Australia’s politicians, however, is the inability to be able to pick and choose between Christian and Muslim refugees.

If Australia does not respond to the latest Rohingya crisis by opening our doors, not only is it simply demonstrating that we are no friend to Muslim people, but that we are also content to fund, and arm, militarised nations in our region.

Sadly, the lives of many Rohingya people are also currently caught up in our brutal offshore detention centres. It is a tragic merry-go-round that Australia does not seem to want to take responsibility for at either end, yet will no doubt be content to benefit from the opportunistic economic rewards.

While the world watches and waits for Aung San Suu Kyi’s silence to break, the betrayal of human rights continues in our own backyard.