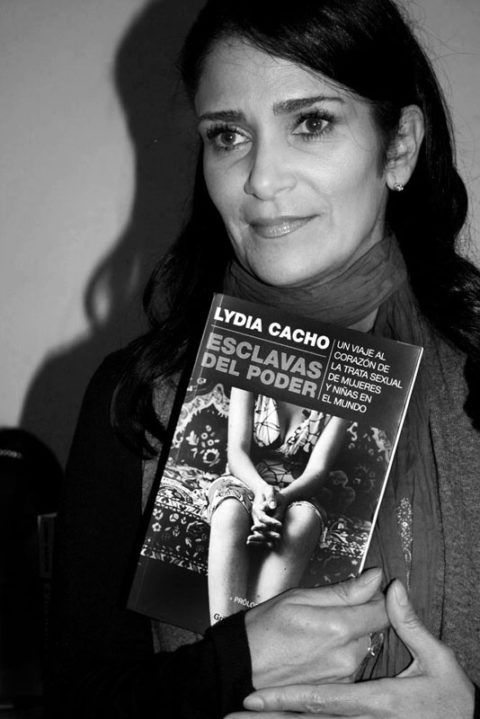

During August and September, Right Now will be doing a series of interviews with guests of the 2014 Melbourne Writers’ Festival. In Part Three of our interview series Ellena Savage speaks with Mexican journalist Lydia Cacho, author of Slavery, Inc., about her work uncovering the global sexual slavery industry.

The other day I was browsing through some internet listicle of women revolutionaries when vanity set in: what would I become, and how would I behave, if a revolution knocked on the door? Would I cower, would I kill? Ugh. What a privilege of peacetime, I thought, to romanticise the necessity of political action.

But perhaps how we characterise wartime and peacetime have little bearing on the lives of women: there is silent war waged against women and girls every day. It’s not sanctioned by any state, not in explicit terms (though it is made possible by governments everywhere), and it’s not negotiated by diplomats or arms dealers. But among the many accumulative acts of aggression against women, there’s an international network of organised criminals exploiting and trafficking girls and women in the sexual slavery industry.

Researched over five years and in numerous countries, Lydia Cacho’s most recent book Slavery, Inc. traverses this dark world.

The preeminent Mexican journalist and activist has been tortured and incarcerated for her work, and consequently lives with the constant threat of assassination. At the risk of imposing macho language onto her, Cacho is a hero of sorts, a person who is standing up against the injustices of her time. She didn’t need a revolution to knock on her door. And I was fortunate enough to speak with Cacho while she was in town for the Melbourne Writers Festival.

Ellena Savage: So I’m writing this up for a fantastic human rights publication. Can you describe some of the human rights work that you do other than your journalism?

Lydia Cacho: Well for almost 20 years now, I have been working on human rights issues: reproductive and sexual rights. I founded a shelter for people with HIV/AIDS in Mexico 18 years ago, and that shelter’s still operating.

I don’t direct it anymore, but I founded it, and I make sure that it will keep on going. And then in 2000 I founded a shelter for women and children who’ve survived domestic violence and trafficking. I centred a lot of the work we did at the shelter and the community centre on legal defence of the victims, because that’s usually the most expensive area, and the one that organisations don’t usually cover. We won some of the most important cases in Mexico and Latin America, including one case of a trafficking ringleader, who was also doing child pornography. He ended up getting a sentence of 112 years, which is the first in Latin America and Mexico.

Do you see your journalism as separate from your human rights work, or is it the same project for you?

Well it’s not the same project, though they definitely link together over time. When I’m doing an investigation or I’m reporting, I’m certainly following the rules of journalism, and when I am involved with the victims as a journalist, and I write about it, I am very honest with my readers. I explain how it goes. I think that all journalism, when you deal with victims and you’re interviewing victims, you’re doing human rights work actually, so it interconnects necessarily. But you have to be very clear when you’re being an activist and [when] you’re being a journalist, and that’s something I’m very aware of.

Your most recent book documents horrific international human trafficking networks. I read in the Guardian that throughout the course of researching this book, your position on the legality and legalisation of sex work changed from being pro-legalisation to being anti-legalisation, is this right?

Yes, ah. I am not an abolitionist as some people are. What I understood after five years travelling around the world and interviewing so many people in the sex industry, I started understanding how we don’t talk about a lot of the things; things to do with the economic factor of the sex industry for example, and inequality.

I went to the Netherlands, because I wanted to understand what happens in countries that have legalised sex work. And what happened throughout the years, I found out for example that in Germany, and the same in the Netherlands, 90 per cent of the sex workers are not German, are not from the Netherlands. They are foreigners, and they are recruited from poor countries where there is no equality, right?

So I asked myself, how come the women from the Netherlands and German women do not want to be sex workers if it’s such a natural and normal and good job? And then again you find out who is handling the legal work of sex workers.

And then there has been a change for a while now, where women who have turned 30 tend to leave the legal market and go out to the streets again, because the market is changing so much, because men are demanding younger and younger women. A woman who is 30, for example, is really old for the business, and is not making enough money to even pay tax. These are some of the things we’re not talking about because when the media talks about sex work and pornography and prostitution, they tend to glamorise the whole thing.

“We have to see that sex is not a personal or individual choice, but a political issue, and a human rights issue.”

Sex work is legal in Victoria, but there’s an ongoing public debate about what it means. Sex worker activists use the language of “choice” to advocate for basically civil and industrial rights. So it can be a hard debate to talk about, without necessarily “speaking for” sex workers. Do you think legalisation ever be a good thing, or is it always playing on gender roles that are already entrenched?

Of course journalists like me, and a lot of journalists I know, we are not talking for them, we are interviewing them, and we are echoing their voices.

But certainly when you interview them as I have, and you see their lives, for example, the teenage years, and when they talk about all the gender violence they experienced, you have to analyse that. You cannot take that away from the reality.

I don’t know if legalisation will eventually be good or not, but there’s such gender inequality in the world. If pornography keeps portraying sex as a very, very violent thing, and if we keep glamorising pornography with teenagers as is happening on the internet, I don’t think we are really solving anything.

The gender gap is still growing around the world, and then you have more and more conservative politicians around the world who are taking away the sexual and reproductive rights of women. What I investigate is organised crime, and what I found around the world, of course even in Australia, is that a lot of this industry is linked to organised crime. We have to talk about that openly.

Feminists have been working towards freedom for women from oppressive structures, but progress has been very slow. In your opinion, what needs to happen in order for women to have freedom?

[Laughs] I wish I had the answer. I would be President of the world if I knew.

Right? But maybe, is it cultures of masculinity that have to change? It feels like women are doing all this work, but that the structures aren’t really changing, so perhaps men have to step up.

Yeah, I think there are many, many things that have to change at the same time. One of them has a lot to do with more men working on masculinity issues. Australia’s one of the countries that has an important group of men doing this, but it’s still a very, very small one, which compared to the men who really don’t give a shit about women’s rights, or who are not really questioning how violence against women is just part of the biggest problem of gender inequality and poverty.

But then also I think that to eventually get real freedom for our granddaughters, we need to go deeper into every aspect of the political arena. We have to see that sex is not a personal or individual choice, but a political issue, and a human rights issue.

And then, of course we need more women in politics, but then what kind of women do we need in politics? The ones who are not buying into the sexist structure. We need women that are feminist to go there and take the philosophy of feminism to the political arena. But I guess that’s the hardest part, because when a women publically says she’s a feminist, then she’s immediately attacked for her beliefs.

“If you think something is not right, fight until it becomes right.”

So would you consider running for a political office?

That’s so funny, that’s the third time someone’s asked me. No, I don’t. I think I’m a good journalist, and I’m a good activist, but I wouldn’t like to be a politician at all.

Yeah, the lifestyle would suck.

I don’t know, I know some women who are amazing at it, and I don’t think I would be good at it. I’m good at what I do, that’s why I do it.

What you do do is quite dark, and you live with the threat of assassination. Do you have some practices that you do in order to deal with the trauma, practices that help keep you grounded?

Of course, absolutely. I’ve been doing yoga for more than twenty years, and I think it’s really important. My mum was a psychologist, so I’ve always been in therapy, and more so since I opened the shelter and I was incarcerated and tortured and all that. I’ve gone through a tremendous amount of work.

There is no way you can become a survivor of any kind of violence if you don’t heal, and unless you have developed more emotional intelligence, and you learn to enjoy life, and have a personal life. Being a feminist and an activist in particular, you can forget your personal life.

Yes, you’re so busy, what do you do in your spare time? Do you take a lot of time off?

Oh, yes. I make sure I get a vacation. I live near the ocean in Cancun, and I love, I need to be near the ocean. I scuba dive, I go salsa dancing, I love cooking, and I have like cooking parties in my house with my friends and stuff like that. That’s something I’ve really cultivated over time, and it’s really important to me.

Do you have any advice you can give other women who are working to overcome sexism in their lives and their fields?

Wow. You’re tough. This is a very deep question.

I don’t know, I think that if you think something is not right, fight until it becomes right. We all deserve integrity and happiness, and when I say happiness, it has a lot to do with economic security, with health, and with safety. And if you don’t have those things, you cannot truly be happy. So you have to fight for that. It’s a right to happiness, and it involves everyday life.