This article is part of Right Now’s March issue, focusing on East Timor.

By Tom Clarke

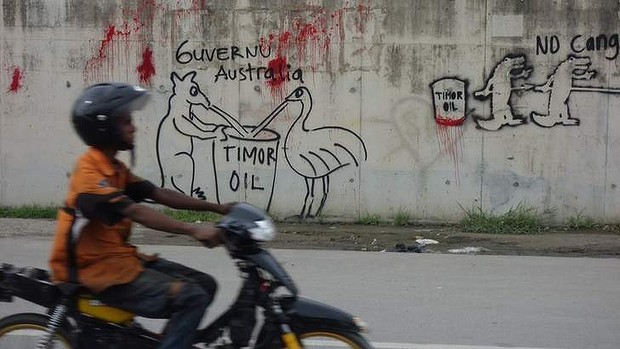

Since the discovery of vast oil deposits under the Timor Sea in the early 1970s, oil has been the ever-present third player in Australia’s relationship with East Timor.

Prior to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor, Australia’s ambassador to Indonesia Richard Woolcott infamously sent a cable back to his political masters in Canberra suggesting Australia’s chances of securing a more lucrative deal over the Timor Sea resources would be better if Indonesia controlled East Timor. It read:

“This could be much more readily negotiated with Indonesia by closing the present gap than with Portugal or an independent Portuguese Timor.”

This set the tone for the next 25 years of Australia’s response to Indonesia’s illegal occupation of East Timor which saw the death of over 200,000 Timorese men, women and children. Australia was all too eager to cosy up to the Suharto dictatorship for political and economic gain.

The 1989 Timor Gap Treaty confirmed this for the world to see.

The treaty was signed by Australia’s foreign minister at the time, Gareth Evans, and Indonesia’s foreign minister, Ali Alatas, as they clinked champagne glasses in an aeroplane flying high above the Timor Sea. Two men divvying up resources that did not belong to either of the nations they represented. It was Timor’s Oil.

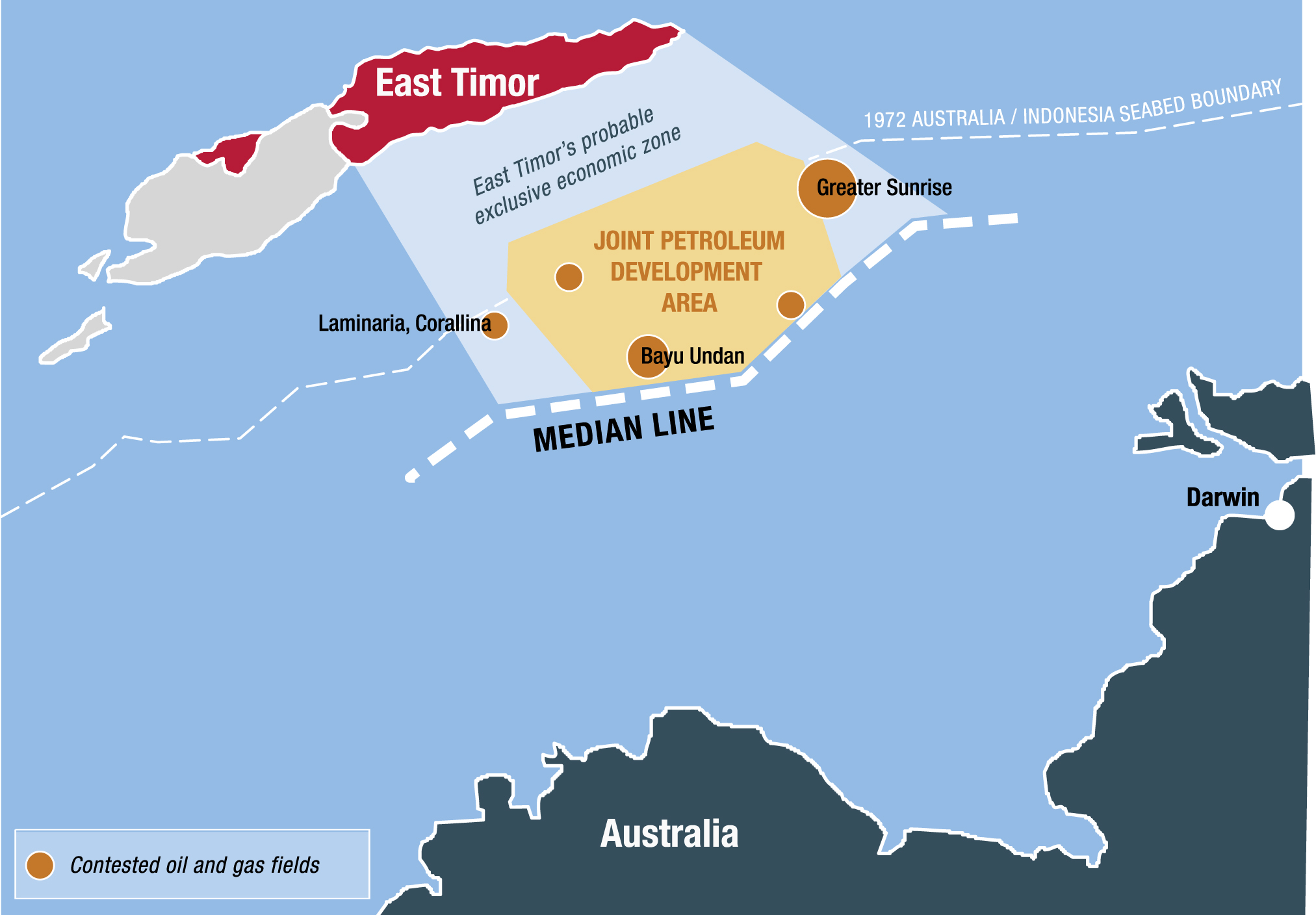

Today, an independent East Timor enjoys 90% of the government revenue from one of the key fields in the Timor Sea, Bayu-Undan. However, the dispute over other significant deposits located nearby is still raging and some deposits, namely the Laminaria-Corallina fields, have nearly been depleted without Timor receiving a cent.

The dispute is likely to continue in one form or another until permanent maritime boundaries are established between East Timor and Australia.

East Timor has never had permanent maritime boundaries. It wants permanent boundaries and, as a sovereign nation, it is entitled to have them. Australia however, has consistently refused to establish boundaries with East Timor. Instead it has jostled our tiny neighbour into a series of temporary resource sharing arrangements – all of which short-change East Timor out of billions of dollars in government revenues to which it is entitled.

To understand the complexities of the current dispute, it helps to step through the various milestones that led to the current state of play.

In 1972 Australia and Indonesia agreed on a seabed boundary. This was based on the now out-dated “continental shelf” argument and the boundary was a lot closer to Indonesia than Australia. Because Portugal, the then colonial ruler of Timor, did not participate in the negotiations, a gap was left in the boundary. This became know as “The Timor Gap”.

Two months after Australia’s ambassador sent the cable mentioned above, Indonesia invaded East Timor and Australia was hopeful the gap could simply be closed and Australia would secure all the riches that the Timor Sea had to offer.

However, Indonesia soon realised it had been “taken to the cleaners” to use the words of its Foreign Minister, Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, and when negotiations regarding the gap began in 1979 Indonesia knew its claim all the way out to the median line had legal merit.

Indeed, in 1982 the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea confirmed median line boundaries as the chosen solution for disputes when opposing coastlines are less than 400 nautical miles apart. Put simply, this means drawing a line half way between the countries.

After a decade of haggling, the Timor Gap Treaty was signed and various “zones of cooperation” were drawn up and Timor’s oil was to be divvied up between Australia and Indonesia.

Australian politicians and the oil companies no doubt hoped that was the end of the matter. However, the bloodshed due to Indonesia’s brutal occupation meant East Timor was never far from the news headlines for the next decade.

Although Australian politicians tried to play down Indonesia’s routine atrocities in East Timor – for example when Foreign Minister Gareth Evens tried to dismiss the Santa Cruz Massacre as a mere “aberration” – the Timorese solidarity movement within Australia and around the world only gained momentum.

The chasm between Australia’s foreign policy towards East Timor and the wishes of the Australian public finally began to narrow at the end of 1999 when Australia led the INTERFET peace-keeping force into Timor in response to the violence unleashed by Indonesia’s unofficial scorched earth policy following the historic referendum for independence.

Many hoped that Australia’s intervention would serve as a great redeeming act and herald a new era in which Australia wholeheartedly respected our newest and tiny neighbour.

It wasn’t to be.

Although Australia has delivered an impressive amount of humanitarian and military support to East Timor since 1999, the amount it has taken in government revenues from contested oil and gas fields during the same period of time is likely to be worth considerably more.

In March 2002, two months before East Timor’s independence, Australia pre-emptively withdrew its recognition of maritime boundary jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

This was an extremely telling decision that signalled Australia had no intentions of playing nice when it came to the placement of maritime boundaries.

Its also makes a mockery of any attempts by the Australian Government to claim that its legal arguments reflects current international law. Turning your back on the independent umpire is not the action of a Government confident of the merits of its own legal position.

On the very first day East Timor’s independence, it signed with Australia the Timor Sea Treaty.

The “Joint Development Petroleum Development Area” that The Timor Sea Treaty created was based on the existing “zone of cooperation” defined by the Timor Gap Treaty. However the 50/50 split in government revenues was upped to 90% in East Timor’s favour. Looked at in isolation, this seemed generous and provided a “feel good” news story for the Howard Government at the time.

The Timor Sea Treaty was expressly meant to be an interim arrangement. It would enable revenues from the Bayu-Undan field to start flowing into the coffers of the fledgling nation without committing it to any permanent boundaries that would need to be negotiated with its neighbours as is the standard process.

However, when East Timor tried to initiate that standard process later in the year by claiming a 200 nautical mile “exclusive economic zone” in all directions based on the principles outlined in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, Australia stonewalled requests to commence negotiations to establish permanent maritime boundaries.

Instead another temporary resource sharing agreement was signed, the Sunrise International Unitisation Agreement, which would allocate 82% of the government royalties from the Greater Sunrise field to Australia. This was despite the field being twice as close to East Timor as it is to Australia.

Revealing yet more hardnosed tactics, Australia refused to ratify the Timor Sea Treaty, signed the year before, until the new deal was signed. This would have delayed production of the Bayu-Undan field and held up the government revenues that East Timor was in desperate need of. East Timor had little choice but to sign the treaty. However, once the Timor Sea Treaty came into effect, Timor understandably did not ratify the Sunrise agreement and negotiations resumed.

The massive Greater Sunrise gas field is located approximately 140 kilometres from Timor and is estimated to be worth at least $40 billion in government revenues. It would most likely be owned entirely by East Timor if permanent maritime boundaries were established in accordance with international law.

During 2004 and 2005 negotiations slowly continued. By early 2005 the Timor Sea Justice Campaign was in full swing. Its grass roots campaigning with WWII and INTERFET veterans, church and student groups, aid organisations and a network of local council “friendship” groups had caught the attention of a businessman named Ian Melrose. Melrose produced and paid for a series of hard-hitting television advertisements highlighting Australia’s “theft” of East Timor’s oil. This blend of local activism and prime-time national exposure was effective in mobilising vocal supporters of East Timor.

In January 2006, East Timor and Australia’s foreign ministers, Alexander Downer and Jose Ramos-Horta, signed the Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea Treaty (CMATS) which would spilt the government revenues 50/50. This increase from the previous plan involving a 18/72 percent split in Australia’s favour came with a major condition: East Timor would shelve its claim for permanent maritime boundaries for the next 50 years.

Woodside Petroleum currently holds the license to develop the Greater Sunrise field. Woodside’s first proposal was to pipe the gas more than 400 kilometres to Darwin for processing. However, this would deprive East Timor of the considerable “down stream” revenues associated with the processing of the gas and this option was vetoed by the Timorese Government who want a pipeline to go to Timor. Woodside’s current proposal is to process the gas on a floating platform near the field.

However, it may be some time yet before the field is developed.

In 2012 a former high-ranking Australian spy came forward with a startling confession. He claimed that he had led a mission to bug the East Timorese cabinet room under the guise of an Australian Aid project. The whistleblower is said to have come forward after learning that Alexander Downer had taken paid consulting work for Woodside Petroleum after leaving parliament.

At the end of 2012, East Timor tried to raise the matter with the Gillard Government but was snubbed by the PM and her Foreign Minister, Bob Carr. So in April 2013, East Timor commenced an arbitration process using a conflict resolution mechanism in the Timor Sea Treaty.

East Timor argues that Australia’s alleged spying during the negotiations of the CMATS treaty gave Australia an unfair advantage and is evidence that Australia did not sign the treaty in good faith. As such, at the arbitration underway in The Hague, Timor is seeking to have the CMATS treaty nullified.

The potential scrapping of the CMATS treaty would see the end of the 50 year ban on Timor pursuing its claim for permanent maritime boundaries.

If permanent maritime boundaries were established in accordance with current international law, East Timor’s probable exclusive economic zone would likely encompass all of the Greater Sunrise field as well as all of the joint development area that Timor currently shares with Australia.

Since the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, international law has overwhelmingly favoured median line boundaries. Yet it is understood that Australia’s preferred option is still to simply “close the gap”.

Former Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, has recently resumed peddling the myth that agreeing to a median line boundary with Timor would somehow “unravel” our borders with Indonesia. This is simply not true as Australia’s borders with Indonesia are set in law and can only be changed with agreement from both nations. Maritime boundaries are set bi-laterally and East Timor will establish is boundaries with Indonesia separately.

Notably in 2004 when Australia and New Zealand established a maritime boundary to resolve overlapping claims off Norfolk Island, Australia agreed to a median line boundary. Evidently, adhering to international law is easier when billions of dollars in government royalties from oil and gas resources are not at stake.

Days before the arbitration about the spying allegations was to commence in The Hague, ASIO dramatically raided the offices of Timor’s lawyers in Canberra who were preparing for the case and also seized the passport of the key witness whistleblower.

This prompted East Timor to launch legal action at the International Court of Justice to insist that Australia hand back the files it seized.

Australia’s Attorney-General, George Brandis, assured the ICJ that he had made undertakings to ensure no one will read the seized files which would give Australia an advantage in Timor’s challenge to the CMATS treaty. In early March, the ICJ issued a provision order confirming that Australia must keep the documents in sealed envelopes until the court has made a decision regarding the legality of the ASIO raids and whether the document will need to be returned.

Notably the ICJ also delivered a clear, binding legal order for Australia not to use national security as an alibi for commercial espionage and insisted that Australia cease inferring with East Timor’s communications with its lawyers. Put bluntly – stop spying on Timor.

In light of all these recent developments, the Timor Sea Justice Campaign has been resurrected and our next campaign meeting in Melbourne will be held on 20 March (details can be found on our website). There are also currently active campaigners on this issue in Sydney, Darwin and Adelaide.

This issue is not one about charity or Australia – it’s about justice. East Timor is simply asking for what it is legally entitled to.

The establishment of permanent maritime boundaries would obviously provide more economic certainty for both countries and for the companies seeking to exploit the oil and gas resources. But perhaps more importantly, it would bring some closure to the Timorese’s long and determined struggle to become an independent and sovereign nation – complete with maritime boundaries.

History tells us that when enough Australians take note and get active, we can change our Government’s policy towards East Timor. If you believe it is time for our Government to finally give East Timor a fair go in the Timor Sea, please get involved or support the Timor Sea Justice Campaign.

For more information, visit: www.timorseajustice.com

Tom Clarke is a spokesperson for the Timor Sea Justice Campaign. @TimorSeaJustice