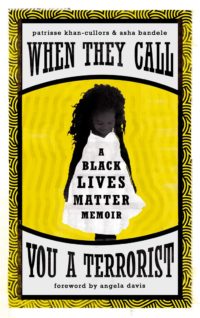

When They Call You a Terrorist

When They Call You a Terrorist

Patrisse Khan-Cullors, asha bandele and foreword by Angela Davis

Allen & Unwin

When They Call You a Terrorist is the memoir of Patrisse Khan-Cullors, key organiser of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. The book is an intensely personal account of the relentless, systemic injustice suffered by African-Americans that ultimately led Khan-Cullors to mobilise the BLM movement in the wake of a series of high profile shootings of young, black teenagers at the hands of police. The movement was not without opposition, ironically being accused of overlooking the importance of other racial groups. Khan-Cullors addresses this backlash through the violent lived-experiences of those closest to her. Recalling an incident where she returns home from dinner with friends to find her innocent husband on the porch in handcuffs, she writes “Later, when I hear others dismissing our voices, our protest for equity by saying All Lives Matter or Blue Lives Matter, I wonder how many white Americans are dragged out of their beds in the middle of the night because they might fit a vague description offered by God knows who.”

In recounting her childhood growing up in Los Angeles, Khan-Cullors illustrates what the systemic disadvantage of African-Americans looks like at every turn. It is the design of a poor, non-white neighbourhood where there are “no green spaces, no playgrounds, no parks for children”, forcing them to explore in the alleyways under constant police surveillance. It is the school that threatens a 12-year-old girl with criminal charges for writing the word “Hi” on her locker. Most chillingly, it is the officers of the State who do not hesitate to trespass on the physical integrity of black children before they have even hit puberty.

“I watch the police roll up on my brothers and their friends, not one of whom is over the age of 14, and all of whom are doing absolutely nothing but talking. They throw them up on the wall. They make them pull their shirts up. They make them turn out their pockets… I watch, frozen. I cannot cry or scream. I cannot breath.”

Another powerful feature of this memoir is Khan-Cullors’ exploration of intersectionality, given her own experience as a queer black woman. She mourns the lack of safe space for her authentic self in her teenage years, facing expectations of criminality in public whilst “feeling the judgement and silence that comes with being Queer in a Jehovah’s Witness home”. However, it is the story of her brother Monte, who suffers from a mental illness, that is the most harrowing account in this book. The intersection of Monte’s gender, race, poverty and disability results in a series of heart-breaking encounters with a criminal justice system that tries its level-best to strip him of all human dignity. In telling this story Khan-Cullors demands the reader to not look away.

“Monte is kept in his cell 23 hours a day in solitary confinement, a condition that has long been proven to instigate mental illness in those who previously had been mentally stable. In my brother’s case, he deteriorates quickly, predictably, horribly and without a single doctor. When I go to the Twin Towers for the first time to visit my brother he makes the plea again. “I don’t feel well, Trisse. Can I please have my meds?”

However, amidst the personal pain and state-sponsored brutality in this memoir, another theme emerges: love. Love of family, love of community and Divine love keep Khan-Cullors’ fighting spirit alive. It is in the story of a father who loves his daughter as best as he can despite his own struggles with alcoholism. It is there in the community of friends that hold space for each other’s struggles when they seem insurmountable. It is there in Khan-Cullors’ lifelong discovery of spirituality, her dedication to finding meaning beyond the religious dogma of her family home. These beliefs form the backbone of a movement based on three simple words to express the inherent human worth of a group whose freedom in the United States has never been conclusively determined.

Cornel West, a prominent black rights activist, wrote “Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public.” In a similar vein, When They Call You a Terrorist is a powerful reminder to activists everywhere about why we persist in an era of rising populism “where we have to fight for the most basic of rights”. Ultimately, the belief in the inherent dignity of man is rooted in compassionate, universal love. This, writes Khan-Cullors, is “what the possibility of the world in which our lives truly matter looks like”.