Wednesday’s High Court decision upholding the legality of detention in Nauru is tragic in its result. But the decision was far from a vindication for the Government. In important ways the judgment signals an increasing willingness by at least some members of the High Court to rein in the excesses of Australia’s detention policies.

The case was litigated by the Human Rights Law Centre on behalf of a Bangladeshi woman brought to Australia while she was pregnant, and centred on two main claims: that no Australian law authorised the government to fund offshore detention arrangements, and that the detention by the Commonwealth Government on Nauru was unconstitutional.

The first claim was fatally undermined because after litigation had started, Parliament rushed through retrospective legislation to authorise the funding of offshore processing. This legislation, which was passed in the dying hours of a parliamentary session with bipartisan support, was critical to saving the Commonwealth. Until that legislation was passed, it appears (as Justice Gageler suggests) that offshore processing was indeed unconstitutional. The passage of this legislation is another example of the Australian Government attempting to circumvent court decisions.

The more interesting aspect of the case was the question of whether the detention on Nauru by the Australian Government was unconstitutional, because of the constitutional limits on the power of a government (rather than a court) to detain people.

Interestingly, the judges did not suggest that the transition to an open centre on Nauru meant that there was, in fact, no “detention”. Nor did the court accept the Commonwealth’s argument (both in court and in public) that it was merely deporting people back to Nauru, and what happens on Nauru is not Australia’s responsibility. Instead, most of the judges found the Commonwealth either detained, procured the detention of, or at least participated in the detention of people on Nauru. This indicates a refreshing willingness of the Court to look behind legal fictions, and demonstrates that Australia cannot escape responsibility by simply exiling people offshore.

Several judges also reminded the Government of the limits to its ability to detain people, limits that the court has been quietly developing in recent years. For example, Justice Gageler held that there must be legislation to authorise the government to detain people on Nauru, which it did not have until the retrospective legislation passed in June.

His Honour also invited a further challenge by reminding the government that detention on Nauru was subject to limits in terms of purpose and duration – that is, people could only be detained offshore for as long as was necessary for processing refugee claims, and that this duration must be capable of being supervised by a court.

In her dissent, Justice Gordon went further and recognised the dangers of allowing a government to do offshore what it cannot do onshore. As Her Honour pointed out:

The Parliament’s legislative powers are not larger outside the territorial borders than they are within the borders. Put another way, [the Commonwealth’s argument] permits Parliament to enact a law allowing the Executive Government to do anything to the person or property of any person who is an alien so long as the conduct occurs outside the territorial borders of Australia. Why is the “aliens” power to be read as circumscribed by Ch III in the case of laws dealing with conduct in Australia but not affected by Ch III so long as the conduct occurs outside Australia?

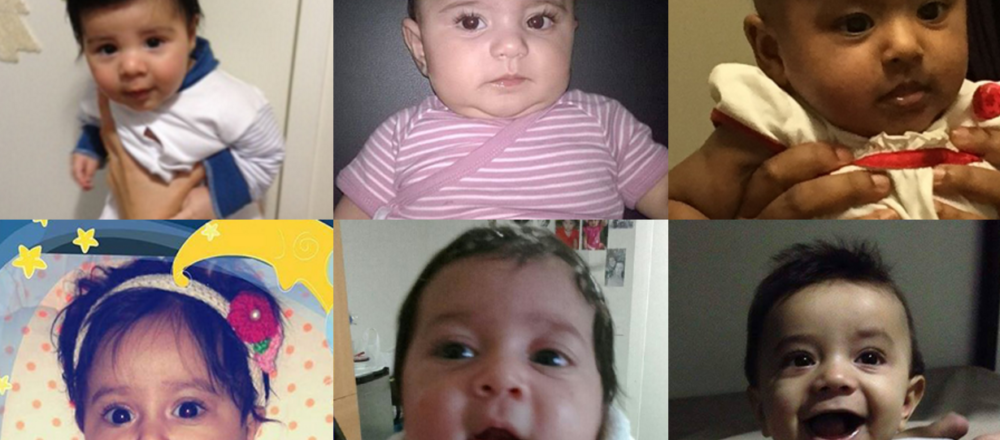

There are silver linings in this latest High Court case. But it also demonstrates the inadequacies of Australian domestic law to protect vulnerable people, and the rule of law itself. While offshore processing remains legally valid under Australian law, Australia’s detention centres (both outside and in Australia) violate international law, as has been repeated by multiple UN bodies and international organisations. The direct result of this judgement is that 267 people, including 54 children and 37 babies, face deportation back to these centres where gross violations of human rights continue to occur daily.

This case reminds us that it is through the political process, and not through the law, that human rights will be best protected. The decision of the High Court found that detention on Nauru was lawful, not moral. Our government can still decide to allow these people, including babies, children and families, to remain in Australia and have their refugee claims assessed here.

As Daniel Webb, Human Rights Law Centre’s Director of Legal Advocacy, said:

The legality is one thing, the morality is another. Ripping kids out of primary schools and sending them to be indefinitely warehoused on a tiny remote island is wrong. We now look to the Prime Minister to step in and do the right thing and let them stay so these families can start to rebuild their lives.

—

Dr Joyce Chia is a Senior Policy Officer with the Refugee Council of Australia

Asher Hirsch is a Policy Officer with the Refugee Council of Australia