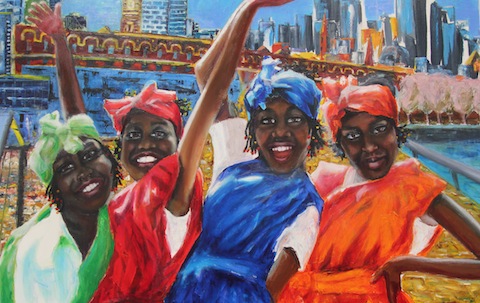

The above image is taken from the Heartlands Refugee Art Prize exhibition. Click here to see more.

This article is part of our July focus on “Australia in the World”. Click here for more articles in this issue.

By Kate Galloway

The recent declaration of the Asian Century underplays the influence and engagement Australia has within the tropics – part of which includes Asia, but which incorporates an even more diverse array of societies. While the tropics can be defined according to climatic and isothermal demarcation, they are more generally considered to lie between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. According to this definition, the tropics include Central and Southern Africa; Northern Africa and the Middle East; the Caribbean; Central and South America; Oceania; South East Asia (including China); and South Asia.

Australia is intimately engaged with its tropical neighbours, especially with Oceania. However given its relative standard of living and ascendant Western culture, the power dynamic is not necessarily an equal one. This is no less so because of the sometimes-mixed messages that emerge in Australia’s “tropical diplomacy”. In Orientalism, Edward Said argues that the “relationship between Occident and Orient is a relationship of power, of domination, of varying degrees of a complex hegemony”.

To what extent might Australia be engaging in a similar dynamic with its tropical neighbours?

Requests of Malaysia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru have in one sense sought to situate Australia’s human rights problem elsewhere.

The diversity of socio-cultural and political environments within the tropics poses a challenge to Australia in terms of its political and human rights engagement there. What provides an additional context for Australian engagement in this region is the history of European intervention in the tropics. Since the European voyages of discovery, the tropics have been sites of colonial occupation.

European imperialism in the tropics

European discovery, followed by imperialism, brought the West into regular contact with the tropics from the 16th century. Since this time, authors such as Mike Hulme and Richard H Grove (and others writing within the field of tropical geography) envisaged the tropics as paradise, as Eden, in the European imagination. The tropics symbolised a contrast to the order and civilisation of Europe and North America.

Imperial expansion saw the West cast a negative projection on to the tropics, which were regarded purely as a site of exploitation for European ends. European competition to control the spice trade is an example of this. Strategic settlements were established to secure trade routes. The Malaysian sultanate of Malacca, for example, was successively ruled by the Portuguese, Dutch and English while Chinese traders continued to operate from the port. The handover from the Dutch to the English was part of a strategic swap of territories during the 19th century, after which the English controlled the Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and Singapore to shore up its trading interests in the tropics.

During the 19th century in particular, European interest in the tropics focused on acclimatisation that in turn drew on matters of race and environmental adaptation. Science was preoccupied with whether the “white man” was “suitable for toil” in the tropics, implying a judgment about differential evolution of the races and thus the suitability of a place for colonisation. David Livingstone for example suggests that the tropics were imagined as an “arena of evolutionary struggle” and “racial survival” where everyday encounters with tropical plants, animals, pathogens, climate and peoples challenged the very existence of the colonial invaders. The presupposition of the higher evolution of the European races was put to the test in such a hostile environment.

Looking at the way in which Australia interacts with its tropical neighbours today, how much has changed? Offshore processing offers a revealing case study.

Australia’s offshore processing and detention policy

Right Now has covered a range of issues raised by asylum seeker policy and debate in Australia. What is of interest here is the call on our tropical neighbours to host offshore detention or processing centres. Requests of Malaysia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru have in one sense sought to situate Australia’s human rights problem elsewhere. And this may say something about Australia’s engagement with these nations. The question may be posed as to what extent we regard our neighbours as equals. In light of historical Eurocentric attitudes towards the tropics, is it possible that contemporary policy embeds the old models of exploitation – this time allowing human rights abuses to be outsourced to Pacific neighbours.

The human rights perspective of detention and processing is clearly set out in the Human Rights Commission’s human rights standards for detention.Criticism of the conditions of detention in Nauru and PNG have been well documented, and the Australian Government’s refusal to allow Human Rights Commissioner Gillian Triggs to inspect the detention centres indicates the sensitivity of the issue. In fact almost no one is permitted to enter these detention centres, including media, thus creating an aura of secrecy. According to a tweet on 9 June however, Australian lawyer Julian Burnside QC left for Nauru for a habeas corpus application on behalf of 10 asylum seekers, as part of a legal team including instructing solicitor George Newhouse, Michael (Dan) Mori and Sydney barrister Jay Williams. Even as lawyers for detainees, the team reportedly had difficulty gaining access to take instructions from their clients.

Likewise, the “Malaysia Solution” was seriously considered despite concerns about Malaysia’s failure to adopt international human rights instruments. Ultimately, the plan was struck down by the High Court based on the failure to ensure asylum seekers “access and protection and the meeting of human rights standards” in Malaysia.

PNG’s own opposition leader is presently challenging the Manus Island arrangements in the PNG Supreme Court, claiming that PNG law only allows lengthy detention of those who have broken the law. The action indicates that the issue is sensitive in PNG as well as in Australia.

While Australia represents itself on the world stage as a model international citizen in terms of human rights, it is willing to hold Malaysia, Nauru and PNG to a lower standard of human rights enforcement even in matters that directly relate to Australia’s own international obligations.

While Australia is prepared on the one hand to enlist the assistance of its neighbours in a policy antithetical to human rights, on the other hand it positions itself as an upholder of human rights in the region. Through its AusAID program for example, Australia seeks to promote human rights in the region: “Enhanced human rights is a pillar of Australian governance support because it is intrinsically linked to justice, accountability and transparency”. This message however is not universally supported by Australian actions in the region.

As an illustration of this, the Australian Government speaks out against the death penalty. It has acceded to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which commits signatory nations to the abolition of the death penalty, and has voted in favour of the United Nations General Assembly resolution calling for a global moratorium on the use of the death penalty.

In spite of this, asylum seekers were to be sent to Malaysia – a nation that imposes the death penalty. The recent decision by PNG to reintroduce the death penalty means that this punishment will apply to asylum seekers guilty of particular offences under PNG law. Australia’s preparedness to send people to jurisdictions in which they may be exposed to the death penalty puts it at odds with its explicit standing on the issue. This is neither “just” for asylum seekers, nor “accountable” to the international community.

Another concern here is the “transparency” of Australia’s overseas detention program. In excising its entire mainland from the migration zone, Australia has not only used a legal fiction to limit its obligations under migration law, but it has outsourced its own declared mandatory detention, further abdicating its own direct responsibility for incarceration of people without charge. Unwilling to wear the political and humanitarian costs of imprisonment on its own shores, Australia argues both that its own sovereignty justifies exclusion of asylum seekers and that the sovereignty of its neighbours puts these people outside its own purview. This is hardly a transparent mode of operation within a human rights framework.

The tropics and the way we think about them, bears the mark of European hegemony through domination and power over its people and environment. Australia is part of that tradition. What Australia’s present engagement reveals is an ongoing use of its power in the region and even perhaps the “evolutionary struggle” embedded in the earlier imperial discourses. In making its neighbours complicit in its own rejection of human rights, there is an echo of Australia’s own assumption of the “otherness” of its tropical neighbours.

Australia as a human rights leader

While Australia represents itself on the world stage as a model international citizen in terms of human rights, it is willing to hold Malaysia, Nauru and PNG to a lower standard of human rights enforcement even in matters that directly relate to Australia’s own international obligations. The question is whether this differential standard reflects a sense of moral superiority in terms of the task of detaining asylum seekers: that such a task is of itself beneath the professed norms espoused by Australia.

In terms of the power imbalance, it is arguable that Australia retains a colonial attitude towards Nauru and PNG reflecting its role as trustee and administrator. In the same way that Europeans colonised the tropics seeking to advance their wealth and trade ties, so too is Australia re-colonising its neighbours to outsource its political problems in a re-affirmation of its sovereignty. Racial survival, itself part of the Eurocentric understanding of the tropics, is thus transformed into the discourse of border protection and the sovereign imperative of, as former Prime Minister John Howard once remarked, choosing “who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.”

While geographically within the tropics, Australia is positioned politically from a Eurocentric perspective. This is reflected in its engagement with Malaysia, Nauru and PNG in terms of asylum seekers. Its lack of insight into its adoption of well-worn narratives of the wildness of the tropics and their contrast to the “civilised” world is an indicator of its lack of genuine leadership in human rights in the region.

A Pacific Solution must be found – but it is no solution to fail to engage our neighbours as equals in the “just, accountable and transparent” adoption of human rights. An inferior or “evolutionary” standard of human rights is simply unacceptable.