This article is a part of our August focus on Homelessness in Australia – you can access more content from this issue here.

By Sonia Nair

“People walking down the street, when confronted by a homeless person, are very often unsure of what to do and perhaps have a subconscious expectation of being assaulted or robbed, combined with a fear of the unknown. Can you imagine what that homeless person is feeling? – Melbourne vannie veteran KNDole”

“People walking down the street, when confronted by a homeless person, are very often unsure of what to do and perhaps have a subconscious expectation of being assaulted or robbed, combined with a fear of the unknown. Can you imagine what that homeless person is feeling? – Melbourne vannie veteran KNDole”

As many as 20,511 people are homeless in Victoria, according to figures recently collated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with the number steadily rising in recent decades. Although homelessness is often defined as when a person is left without a conventional roof over their head, and the economic and social support that a home typically affords, Melbourne Homeless Services says “homelessness is a universal journey, and is not necessarily by definition just about shelter, it is an intrinsic state of unrest”.

Through its frank, incredibly personal and raw stories, Soup Van forces readers to consider the way they treat homeless people and how much they truly know about [them].

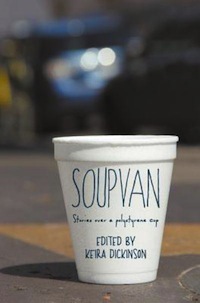

This “intrinsic state of unrest” is rendered a face in nuanced autobiographical accounts of both ‘vannies’ (volunteers) and ‘streeties’ (soup van patrons) in Soup Van: Stories over a Polystyrene Cup where depictions of physical abuse, sexual exploitation, abandonment, neglect, mental illness, reliance on illicit substances and prostitution interlace amongst one another to paint the reality of marginalised Melburnians that often frequent, and seek refuge at, soup vans.

Through its frank, incredibly personal and raw stories, Soup Van forces readers to consider the way they treat homeless people and how much they truly know about the significant subsection in which they share their city with. But perhaps the book’s biggest strength is how it compels readers to consider a reality far removed from that of the typical Australian, yet not entirely unimaginable – encapsulated in editor Keira Dickinson’s prologue.

“Don’t ever give up on anyone; be kind to people. Because under different circumstances it could have been you.”

Apart from the personal accounts, it is through the vannies’ eyes that we learn more about the lovable and resilient, yet severely disenfranchised, patrons of the soup van. Readers are first introduced to soup van patron Terry – a man who was brought up by an alcoholic father and eventually imprisoned when he was a teenager for stealing a ute – in a loving ode penned by 30-year vannie veteran David Disher. Whether it is by scaring ticket inspectors off with mice or entering competitions with odd questions like ‘what’s a communist?’, Terry ingratiates himself with the vannies through his compassion, comic timing and his ‘famous cackle’ – with the unassailable spirit of similarly downtrodden streeties emerging as a common thread by the end of the book.

“In my view Terry had been completely broken by a system that let a child fall through the cracks and then enter an adult world via one of its worst institutions.”

Similarly abused by a system that allowed Aboriginal children to be taken away from their parents in what became known as the Stolen Generation, streetie Nedja reflects on how soup vans transcend food and drink and become a safe haven where friendships and deep bonds are inexplicably formed.

“Aboriginal, white person, Chinese, Greek, Italian, everyone. A lot of people like that run around Fitzroy. And everyone knows each other. And when soup van comes they all come together.”

It is a sentiment that runs rampant throughout the book, as streetie-cum-vannie Kim reflects on how soup vans helped her stay afloat when she was a sex worker in St Kilda.

“Things change, but the people on the soup van were, and always are, still unique. There are not many people like that. Every single one of them is a decent person. It’s not always the way, no judgement and lots of time, when you need help.”

Further afield, Serbian immigrant Miroslav Paunov’s recollection of how he was raped by a neighbour and later abused because he was a homosexual living with HIV – finally escaping to Australia – is just one of the many harrowing autobiographical accounts in the book that illustrate how often people are catapulted by a series of haphazard events into a seemingly unstoppable cycle of abject poverty and homelessness.

It is a sentiment that is voiced again in ‘Family History in My Coles Bag’ where vannies sadly wonder when soup van patron Ethan’s life took a turn for the worse as he presents them a photo album of his family.

“A photo of Ethan as a baby, a professional photoshoot for his christening, with him in a white gown and his parents on each side, looking thrilled and proud. Their first child. We looked at the picture intently, trying to work out where things went wrong for him.”

In testament to the beautifully penned and painfully candid accounts, we fall in love with Pat, who plucks the hairs from the legs of unsuspecting painters; we resonate with the fear vannie Rebecca Armareggo felt on her first day as a volunteer; we cheer as streetie Steve saves up enough to own something he loved – a caravan – and we cry as streetie Matthew dies in his sleep.

By conferring a face to the many homeless people that live within Melbourne and their incredibly multifaceted lives, unyielding aspirations and zeal for living, Soup Van’s beauty is in the humanity and compassion it accords a subsection of society often overlooked and misunderstood by the wider community and system it lives apart from. But perhaps the line that best encapsulates the virtue of soup vans for both vannies and streeties is this:

“It was obvious that you can become ‘family’ by other means than being born into one.”

Excerpt – ‘The Birth of Miroslav Paunov: Part 1’

Why did you leave your village in the first place?’

‘The village I was born in was flat as flat, like Kansas in America. Field after field, wheat and corn and sugarbeet. I watched it and I smelled different smells, I don’t know how I smelled them. And I heard different sounds. I don’t know how I heard them. And I was adventurous. I always thought, over the horizon, there must be something better. Something different.’

He was lost to that thought for a moment. Then suddenly Miroslav said:

‘How shocking it was when I came so many years later in this country, not speaking the language, don’t know anybody, no money, no job. I was told I would be educated in English and introduced to a good job. They didn’t do what they promised! I was twenty-six, twenty-seven when I got to Australia. I was in Vienna before that. I ran away to Vienna after I had to do army service in Serbia. That was hell.’

‘What was hell? The army service?’ He nodded.

‘Talk about bastardisation, bullying. What kids experience in school. Kids commit suicide because of it. That was going on. I was too short, plus I was a gay. They found out because I fell in love with another man during my army service. You can’t go against nature, no matter how much you should in a situation like that. He was away for one year and a half from his girlfriend, so he probably felt the same. But he wasn’t really gay, he wasn’t, but he knew what I was. So it was an experience. But afterwards, when people found out he sort of pushed me aside, and he got embarrassed and he said that I attacked him. And he was twice as big as me!

‘That’s how it is.’