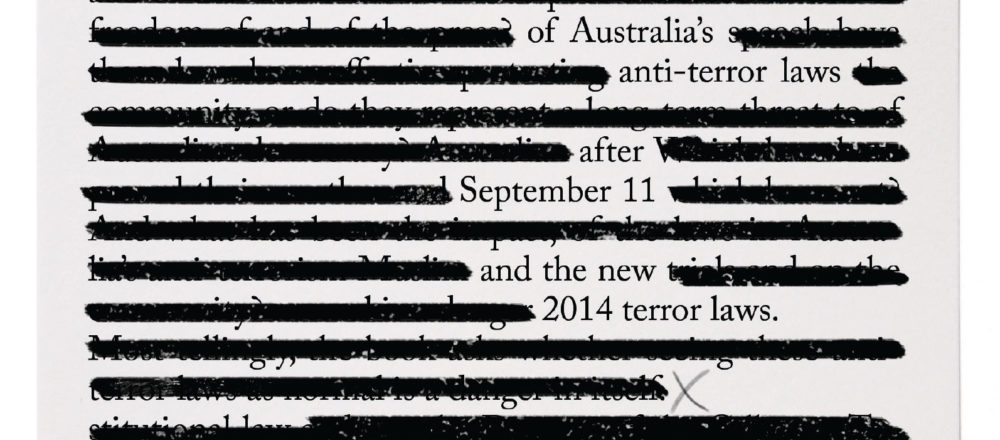

Inside Australia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws and Trials | Andrew Lynch, Nicola McGarrity and George Williams

In the weeks and months following the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington D.C., governments and citizens around the world were understandably nervous about the adequacy of existing domestic legislation to protect citizens from similar acts of terrorism in their own countries.

In Australia, one of the Coalition government’s first responses was to introduce a bill into parliament which sought to give the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) the power to strip-search and detain adults and children who were not suspected of any wrongdoing but may have information of interest to the intelligence organisation, for an (infinitely renewable) period of two days,.

The detainees were to be given no right to legal representation and no chance to inform family members of the reason behind their sudden disappearance. Unsurprisingly, in response to this, comparisons to Cold War-era dictatorships abounded in public commentary.

Due to staunch opposition, a revised and watered down version of the law was passed 15 months after its introduction into parliament. Still, no other comparable nation such as the United States, Canada or the United Kingdom has thought to endow a domestic intelligence organisation with such a power.

ASIO’s new question and detention warrants are just one in a myriad of bills, acts and amendments comprising Australian anti-terrorism legislation that is summarised and scrutinised in a new book by Andrew Lynch, Nicola McGarrity and George Williams AO, Inside Australia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws and Trials.

Their work seeks to clearly and concisely outline the 64 separate pieces of anti-terrorism legislation that have become law since September 11, up to and including the Abbott Government’s recent laws passed in late 2014. Despite the convoluted nature of this body of legislation, the authors present a very accessible summary of the nature and basic implications of these laws. Ordered thematically, these include: the legal definition of a terrorist act; criminalising terrorist acts and the conspiracy to commit a terrorist act; associating with and funding terrorist organisations; foreign incursions; the prosecution process; and the powers of the police and intelligence agencies.

The authors also dedicate a large portion of the book to exploring control orders – a controversial power that was given to the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in the wake of the 2005 terrorist bombings in London.

With approval from a court, control orders allow the AFP to place restrictions on the movement, communication and other activities of people who may pose a terrorist risk to the community whether or not they have been found guilty of, or are suspected of, committing a crime. As the authors note, “this is more than a breach of the old ‘innocent until proven guilty’ maxim: it positively ignores the notion of guilt altogether”.

One point of view that does emerge clearly throughout the book – and an issue that author George Williams has addressed extensively in his own body of work – is the need for an Australian Bill of Rights.

In addition to presenting a succinct overview of anti-terrorism legislation, the authors also seek to determine whether anti-terror legislation “meets the threat in a proportionate way – that is, whether it aims to achieve security without unnecessarily diminishing the freedoms which are the hallmark of an open democratic society”.

However, it is often in this more interesting and original endeavour that the authors unfortunately fall a little flat. Throughout the book, passing remarks about the difficulty in striking a balance between security and liberty arise more commonly than in-depth insight into the implications of these highly contentious laws. Overall, the impression of the book is more descriptive than argumentative.

One point of view that does emerge clearly throughout the book – and an issue that author George Williams has addressed extensively in his own body of work – is the need for an Australian Bill of Rights. This argument is particularly clear when it comes to assessing the human rights risks surrounding control orders.

As the authors explain, the changes to criminal legislation that were brought about in 2005 were based directly on laws that had been introduced in the United Kingdom to establish a regime of control orders earlier that same year. Yet, in the United Kingdom, a national Human Rights Act limits the legal system’s ability to impinge on human rights and since the law’s initial introduction, control orders in the UK have been subject to constraints due to various legal applications of this Act. Conversely, in Australia control order legislation has been strengthened over time despite similar concern for human rights emanating from the general public and other regulatory bodies.

Although the authors’ discussion of the human rights and other implications of anti-terror legislation may be at times brief and greatly simplified, Inside Australia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws and Trials remains an excellent introduction to this new area of criminal law and to some of the issues surrounding its nature and application.

As the authors themselves note, many of these highly controversial laws have been introduced as a “hasty, knee jerk reaction to catastrophic events overseas” with little serious consideration of the intrusions upon personal liberties. A greater public understanding and discussion of these laws is crucial if we are to fight for the protection of our democratic values and human rights.