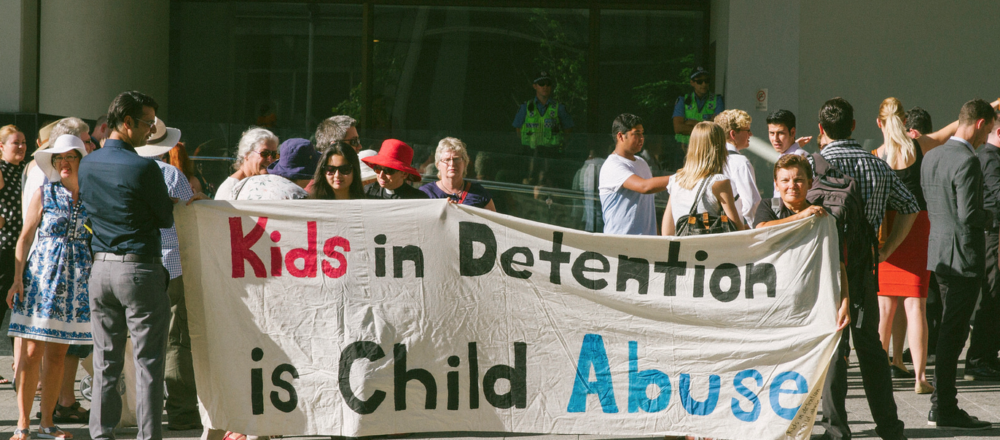

With the number of children in Australian-run immigration detention centres significantly lower than this time last year, it might seem reasonable to ask why organisations like ChilOut – Children Out of Immigration Detention – continue to campaign with the same intensity. The cross-party Senate report into the Nauru detention centre released earlier this week, which revealed widespread allegations of child abuse, should give you some idea.

First, despite perceptions that all, or almost all, children have been released from detention, there are still over 200 children in immigration detention in both Australia and Nauru. Second, although the number of children in detention is significantly lower than its peak of 1992 children in July 2013, evidence concerning sexual and physical abuses against children continues to mount and children are spending record periods of time in detention. Third, without changes to current law, which still provides for the mandatory detention of adults and children who arrive in Australia by boat, statements by the Government or the opposition about their intentions to release children or keep them out of detention cannot be trusted.

A bit of history

The mandatory detention of asylum seekers in Australia was introduced in 1992 and originally intended as a temporary, exceptional measure in response to Indochinese asylum seekers coming by boat. The policy was extended in 1994 to all “unlawful non-citizens” and time limits on detention were removed. Australia became the first and only country in the world to enshrine mandatory detention in legislation.

Over the years, Australia added offshore processing to the policy mix. First introduced in 2001 and initially known as the “Pacific Solution”, offshore processing was subsequently abolished, only to be re-established under a different Government in 2012. Since then, asylum seekers have been transferred to detention centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

In June 2005, growing public pressure and relentless lobbying by human rights and community groups led to then Prime Minister John Howard softening Australia’s treatment of children in detention. It was no coincidence that a year earlier, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) had released its first major investigative report into children in immigration detention. Amendments were made to the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) to introduce the principle that children should only be detained as a last resort. Within a month after the amendment came into effect, all families with children had been released from detention facilities, and moved into residence determination arrangements within the community.

After the release of children in 2005, ChilOut ceased its work and was formally commended by the AHRC for its role in the campaign. Unfortunately, however, ChilOut’s job was not done. It became apparent that the legislative amendment on children in detention introduced by the Howard Government was intended to give the Minister for Immigration a broad discretion and was a loose guiding principle with no legal enforceability.

With a change of Government and shift in policy, children seeking asylum were once again locked up in Australian-run immigration detention centres. In 2010, with the number of children in detention rising and the length of time children were spending in detention increasing, ChilOut decided to recommence its work. The major lesson was that legislative reforms that mandate a maximum period of detention are vital in order to guarantee that children are detained as a measure of last resort and for the shortest possible amount of time.

“No other country mandates the indefinite detention

of children when they arrive to seek asylum.”

Where we are today

At the end of 2014, the Government promised to release all children from immigration detention facilities by early 2015 (part of a deal to get harsh new asylum seeker measures passed in the Senate). The deal was struck just a few months before the AHRC’s second major report into children in immigration detention was tabled in parliament in an attempt to pre-emptively address the report’s recommendations.

Yet despite the Government’s promise, 205 children remain in closed detention facilities as at 31 July 2015. The number of children in detention has, in fact, remained almost stagnant for the past four months. Though Australians do not like to think of themselves as especially harsh or inhumane, contrasts with other countries are stark. The fact is that no other country mandates the indefinite detention of children when they arrive to seek asylum.

For example, in 2014 the United Kingdom amended its Immigration Act to ensure that detention of children is limited to 72 hours at specially designated accommodation. In “exceptional cases”, detention may be extended to one week, but only with authorisation from the relevant Minister. Unaccompanied children may not be detained for more than 24 hours and additional conditions must be met to detain an unaccompanied child for even this brief period. In Sweden, the Swedish Aliens Act states that children may only be detained for 72 hours, with a further 72 hours available in exceptional circumstances. Statistics show that the average length of time that children spent in detention in Sweden in 2013 was just five days. Unlike Australia, for these countries the detention of asylum seeker children truly does seem to be a last resort.

The way forward

In order to protect and respect the basic human rights of children seeking asylum there must be a legislative time limit on the detention of children. For ChilOut, that means amending the Migration Act to ensure that no child is detained in any Australian-run immigration detention facility for longer than seven days.

Ending immigration detention of children is possible. We did it ten years ago and we can do it again. This time, however, we must ensure that it is accompanied by appropriate legislative changes so that the pendulum does not keep swinging between a small number of children in detention and thousands of children in detention. Children do not belong in detention at all.

ChilOut is committed to continuing its fight until every last child is released from Australian-run immigration detention centres, and there are legislative safeguards in place to ensure that no child is ever again detained for prolonged periods.

—

Claire Hammerton is a human rights lawyer and Campaign Coordinator at ChilOut (Children Out of Immigration Detention). She is also a National Committee Member and Refugee Subcommittee Coordinator with Australian Lawyers for Human Rights.

This article was originally published by Asylum Insight. Read the original article.

To find out more about the number of asylum seekers in detention, visit Asylum Insight’s statistics page.

Feature image: Love Makes A Way/Flickr