HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MEDIA: OCTOBER 2013

By Pia White

October’s focus on the responsibility of institutions to uphold and respect human rights leaves plenty of room to examine the media’s place in such a philosophy.

Detrimental Discourse

The human rights challenges surrounding asylum seekers are well documented, with questions regarding the discord between the right to seek asylum and Australian mandatory detention and deterrence policies routinely and rightfully posed.

Though the directive from Morrison extends only to the bureaucracy, it has been argued that the media is also complicit in perpetuating this type of language …

Over the past month, the debate’s focus has shifted somewhat from what is being done to what is being said, after Immigration Minister Scott Morrison’s directive “instructed departmental and detention centre staff to publicly refer to asylum seekers as ‘illegal’ arrivals and as ‘detainees’ rather than as clients.”

The use of such language has been widely criticised including by Julian Burnside, Asylum Seeker Resource Centre chief executive Kon Karapanagiotidis and Bishop Phillip Huggins, with a common chorus being that of the dehumanising effects of such terms and their connotations of criminality and wrongdoing.

Though the directive from Morrison extends only to the bureaucracy, it has been argued that the media is also complicit in perpetuating this type of language, despite discouragement from the Australian Press Council.

Given the profound capacity for discourse to shape attitudes, we should hope that the Australian media heeds calls for compassion to be extended to the plight of asylum seekers and shies away from the inflammatory language advocated by the government.

Constitutional Challenge

The question of language also factors into discussion of same-sex marriage with the challenge to the Australian Capital Territory’s marriage equality law centring on its potential inconsistency with the definition of “marriage” under the Marriage Act 1961.

On Tuesday 22 October, the ACT became the first Australian state or territory to legalise marriage between same-sex couples. However, the federal government had made it clear even before its successful passage through the Legislative Assembly that it intended to challenge the validity of the law in the High Court, and then proceeded to lodge its objection the day after the law was passed.

The necessity of framing the marriage equality debate in this way, rather than as a matter of discrimination or human rights, comes down to the absence of an Australian federal bill of rights …

The upcoming constitutional challenge will centre on whether the Marriage Equality (Same Sex) Act 2013 is inconsistent with federal marriage legislation and debate regarding the issue has largely focused on whether this area should be regulated nationally and uniformly or by the states and territories.

The necessity of framing the marriage equality debate in this way, rather than as a matter of discrimination or human rights, comes down to the absence of an Australian federal bill of rights, like those that exists in many other places in the world. Arguably without such a legislative resource, the role played by institutions in defending human rights in Australia is more profound that it otherwise would be.

Institutional Inequality

To call the entrenched inequality between the indigenous and non-indigenous communities in Australia as enduring seems an inadequate way to describe what has become a horrifying status quo. The disproportionately high incarceration rates of indigenous Australians are a notable example of what can be described an institutional discrimination.

… figures suggest that the increases to the numbers of incarcerated indigenous Australians is attributable to “mainly to changes in the criminal justice system’s response to offending rather than changes in offending itself.”

Earlier this month, the High Court delivered an important judgement that will allow a person’s social disadvantage to be considered during sentencing, but that this was to be applied “in every case irrespective of an offender’s identity or … membership of an ethnic or other group.” While this could be argued to be an intuitional attempt by the judiciary to address systemic disadvantage, still not enough is being done.

In an SBS radio interview, Felicity Graham of the Aboriginal Legal Service pointed to the failure of this measure to take account of the “over-representation of Aboriginal people in detention.” She also highlights that NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research figures suggest that the increases to the numbers of incarcerated indigenous Australians is attributable to “mainly to changes in the criminal justice system’s response to offending rather than changes in offending itself.” Additionally it has been suggested that indigenous Australians suffer harassment at the hands of authorities, with policing that “zeroes in on Aboriginal men and women.”

Such accounts therefore undermine the High Court’s actions and raise questions as to the wisdom of relying on institutions to cure themselves systemic injustice.

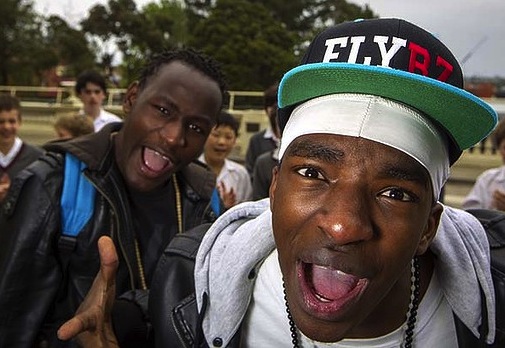

FLYBZ – ‘CHILD SOLDIER’

By Sam Ryan

Paul Kelly’s immediately recognisable vocals have told hundreds of stories in song, but ‘Child Soldier’ – launched last week – is surely the first time he has lent his voice to the lyrical narrative of a child soldier and refugee.

Paul Kelly’s immediately recognisable vocals have told hundreds of stories in song, but ‘Child Soldier’ – launched last week – is surely the first time he has lent his voice to the lyrical narrative of a child soldier and refugee.

The song is the work of Melbourne hip-hop duo FLYBZ, consisting of 21-year-old Fablice and his nephew, 17-year-old G-Storm. That they are being noticed and working with the likes of Paul Kelly at such a young age is an achievement in itself, let alone that their childhood revolved around civil war and refugee camps with little access to music.

In ‘Child Soldier’ they hold nothing back, but find a balance through the music between despair and hope.

It was in the Tanzanian refugee camp where the pair lived in 2003 that they saw 50 Cent and were inspired to tap into music as a means of expression.

But while 50 Cent often occupies his songs with “bling” and “girls”, Fablice says the he and G-Storm are focused on the message of freedom.

Talking to Right Now Radio about his experience as a child soldier and escape from Burundi, he said that “the conflict that ive seen going on between my brothers and sisters with no reason, always pushes me to feel like I need to put it out there so people can hear it, because we people who live around here we are the ones who can make a change”

In ‘Child Soldier’ they hold nothing back, but find a balance through the music between despair and hope.

“Killing, raping, gang fighting every night, everyone living in constant fright,” G-Storm raps, while Paul Kelly’s refrain “All he wants is love” emerges from the background, backed up by chilled-out, if sorrowful, beat, guitar and trumpet.

This is a song that can be easily enjoyed on a musical level, with truly confronting lyrics when listened to closely. That’s the power of music, a power FLYBZ have impressively harnessed.

View the ‘Child Soldier’ video below.