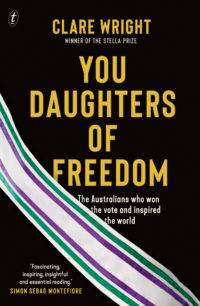

You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World

Claire Wright

Text Publishing

Reading Clare Wright’s history of the suffragette movement in Australia and Britain, I was frequently struck at how history repeats itself. For example: A Prime Minister who refuses to listen to facts or respond to political will. Protest marches with increasingly large numbers; protest action becoming militant in response to belligerent leadership; escalating punitive measures from authorities. This was the political atmosphere in Britain, in the first decade of the previous century. It sounds depressingly familiar.

At over 479 pages, You Daughters of Freedom may look like a daunting read. Wright provides comprehensive coverage of events from 1891 to 1918 (the year that British women finally won the right to vote). She deftly keeps the story interesting, presenting it largely through the activities of five Australian women who played key roles in the Suffragette campaigns in Australian and Britain: Vida Goldstein, Dora Montifiore, Muriel Matters, Dora Meeson and Nellie Martel.

Dora Montifiore’s political activism was spurred by learning, after her husband passed away, that “in law, the child of the married woman has only one parent, and that is the father.” Many women (two thirds of women in Victoria, according to Wright) were earning their own living and required to pay tax, yet they could not vote. This was the legal position of women in Britain and the British colonies towards the end of the 19th Century. The five key Australians in this book, and many suffragettes, were motivated to action by a long-term vision of women having an equal say in legislation that directly affected women.

Heated debate around the pros and cons of giving women the vote occurred in social circles, amongst suffrage organisations, and between MPs on the floors of Parliament (in Australia and Britain). Wright reminds us of the attitudes of the time, in relation to women: (“women would become ‘manly’, they would stop having children, they were too emotional…they would only vote as their husbands directed, they would only vote for the most handsome candidate…”) and also, in relation to Indigenous Australians. Below is an excerpt from the Hansard transcript of discussion in Parliament in 1902 about whether to exclude Australian Indigenous people from the vote:

“GLASSEY: What progress have the aborigines made?

PLAYFORD: That is no reason why we should take away from them what is their right.

GLASSEY: Simply because they have been here for a number of years we are asked to enfranchise them.”

The Commonwealth Franchise Act, granting suffrage to most women, was voted in, in both houses of Australia’s parliament, on 29 May 1902. Wright points out that Australia did not vote for universal suffrage on this date. To our shame, the exclusionary clause, hotly debated (as above), was passed, reading: “No aboriginal native of Asia, Australia, Africa or the Islands of the Pacific except New Zealand.” Says Wright: “It was now race, not gender, that defined the limits of Australian citizenship.”

In Britain, the fight went on for sixteen more years. Political action became militant, when attempts to sway Prime Minister Asquith with organised campaigns and displays of political will, came to nothing. Australian women played leading roles through all stages of campaigning.

Financially independent Dora Montifiore, living in London, advocated for peaceful resistance, and publicly led the tax refusal campaign. She was barricaded inside her house, under guard, for weeks, until debt collectors took away her furniture. Muriel Matters was the star in an intervention, strategically planned to occur while British parliament was in session. As a speaker held the floor, she theatrically stood up in the Ladies’ Gallery, unfurled a hidden chain, padlocked herself to the metal grille that partitioned the ladies in the gallery above from the action on the floor below, and began to loudly recite a prepared script, demanding votes for women.

Such exploits sound daring – they were more daring than we might think, as women exposed themselves to violent repercussions. As Ms Matters was being escorted away by police, Wright reports that “One of the policemen had his hand around her throat.” Matters was imprisoned for a month; joining many suffragettes who braved horrendous prison conditions, some repeatedly.

Wright’s research appears to be meticulous. Drawing from reports in newspapers, transcripts from Parliamentary sessions, newsletters produced by women’s’ suffrage organisations, biographies, and personal journals, she gives us detailed descriptions of incidents that usually centre around one of the five Australian women at the heart of the book. We are informed by the facts and kept enthralled by the women’s determination and energy for the cause.

It is heartening to be reminded that so many women were so courageous, determined and outspoken about their collective rights in an era where women were expected not to stray from the domestic realm. Middle-class women (and men who supported them) were spurred by a strong sense of humanitarianism and philanthropy – fighting not to directly improve their own already comfortable lives, but the lives of working class women who could not join protest marches or refuse to pay taxes, because they needed to retain their factory jobs, to support their families. Said Dora Montifiore:

“ I was forced by a sense of duty towards other women who were not so free as (I) was, to act publicly in the cause that was dear to (me), in order to help bring about before the public the question of the gross disabilities under which women were suffering.”

To anyone unfamiliar with the fight for women’s suffrage in Australia and Britain, it’s worth reading this book now, because its underlying message about the power of political action is optimistic and hopeful. As protests about inaction on climate change take place in increasing numbers all around the world, it was good be reminded that these women got together, “discussed and rebelled, and longed to make things better for our children.” And in the end, they beat the cynics and the disbelievers.