By Sonia Nair.

“People smugglers are engaged in the world’s most evil trade and they should all rot in jail because they represent the absolute scum of the earth. People smugglers are the vilest form of human life. They trade on the tragedy of others and that’s why they should rot in jail and in my own view, rot in hell.”

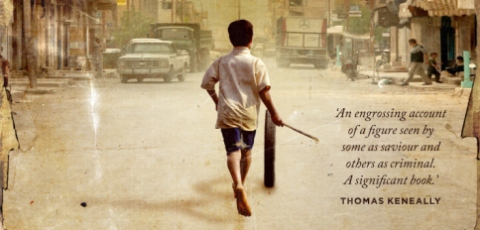

Sentiments such as this, expressed by former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd after a fatal boat blast in April 2009, bestow moral judgement on a difficult choice that few Australians will ever have to make and an inexplicable situation few can resonate with. In The People Smuggler, Sydney filmmaker and writer Robin de Crespigny confers a face to this human tragedy in the form of tailor, freedom fighter and people smuggler Ali Al Jenabi.

In a testament to De Crespigny’s sublime writing style – each act of torture, death, and defeat is treated with the significance and sadness befitting the atrocity…

Born in southern Iraq in 1971 – while Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical rule was still burgeoning undetected by the masses – Al Jenabi led an idyllic life characterised by a gallant father, a doting mother, multiple siblings and a peaceful village. Much like Sudanese refugee Majok Tulba’s Beneath the Darkening Sky however, a sense of foreboding looms amid the happy narrative as readers steel themselves for atrocities that are yet to happen.

Renowned for his non-conformist views, Al Jenabi’s father’s disappearance kick-starts a heinous cycle of pain, suffering and sacrifice that persists for much of the novel. Thrust unexpectedly into a head of the family role, Al Jenabi shoulders a lifelong duty to take care of his family that spans across wider Iraq, the Kurdish-controlled sphere of northern Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and finally Australia as he assumes a number of occupations to guarantee his survival, including people smuggler.

In a testament to De Crespigny’s sublime writing style – each act of torture, death, and defeat is treated with the significance and sadness befitting the atrocity as De Crespigny steers clear from sentimentalising each incident or normalising instances of horrific violence with superfluous depictions of blood and gore.

“All night we scratch until our skin almost comes off, but the more we scratch, the worse it gets. We are like a seething pack of human maggots on the floor, tearing at ourselves, unable to sleep.”

By employing a first-person perspective, Al Jenabi’s factual narrative assumes the feel of a memoir – imbuing the account with an intimacy that would be bereft otherwise. And despite the lengthy narrative, the suspense never abates as readers tether on the edge with Al Jenabi as he escapes the clutches of death time and time again.

“If I broke someone’s law, it was for something good. I provided a path to safety for people who had few other options.“

Like Al Jenabi, each character within the book is a master of their own destiny as De Crespigny resists the urge to paint her characters as victims – despite the limited opportunities offered to them – and exudes self-determination in a time where individualism was continually quashed.

In Al Jenabi emerges an unlikely hero full of contradictions – unafraid of violence when it comes to pigheaded authorities but unwilling to ever use it on the less fortunate, dictated by his family’s needs throughout yet resolute in his desire to take care of them and, despite being surrounded by deceit and mistrust in his native homeland, willing to surrender his heart and extend his friendship to the most unlikely time and time again. Meandering across the most dangerous and morally ambiguous paths, Al Jenabi never loses sight of who he is, and what he stands for.

The themes of “the white man’s burden” and cultural imperialism characterise much of Al Jenabi’s narrative as he cynically muses on why the Americans belatedly decided to “save” Iraq after bearing witness to decades of Saddam Hussein’s despotic ways.

“But there is no evidence of these weapons or Al Qaeda in Iraq, and we have lived under Saddam’s repression for over two decades without any show of concern from the West. That is, until America fell out with him over chemical weapons and Kuwait, and their access to our oil was in jeopardy.”

“There is little talk of what the refugees are running from, or recognition that most of them would prefer to die in the ocean while attempting to escape than at the hands of torturers or executioners in their own country.”

In similarly prized excerpts throughout the book, Al Jenabi displays an astonishing degree of self-awareness and civic consciousness as he ponders the politics of bureaucracy that obfuscates justice, and self-reflection and magnanimity towards those he helped who eventually wronged him.

“If I broke someone’s law, it was for something good. I provided a path to safety for people who had few other options. Maybe Mr Howard thought what he did was good too, but the majority of Australians and millions of people around the world didn’t think so…Why am I more of a criminal than him? He has more blood on his hands than me. I see it every night on the TV.”

“They announce with renewed intensity that this disaster was entirely the fault of people smugglers, who must be stopped in order to save lives like these. There is little talk of what the refugees are running from, or recognition that most of them would prefer to die in the ocean while attempting to escape than at the hands of torturers or executioners in their own country.”

An incredibly important piece of literature, The People Smuggler tackles the uncomfortable realisation that human rights violations take place within our own borders. It expertly delves into the ineffectual immigration officials, the warped border protection policies, and the selfishness that affects many of our politicians.

However, if redemption is what readers want after reading such an account, De Crespigny does not gift it to them. As much as Al Jenabi’s life improved from what it was, scars of his yesteryears haunt him and lives continue to sit in ruin as he struggles to carve a life for himself in his new homeland.

Far from making an ideological standpoint that each people smuggler is a good person – Al Jenabi himself was hoodwinked by many and eventually betrayed by one, The People Smuggler forces us to consider the multifarious factors that propel people to do what they do instead of painting each person with the same tarred brush.