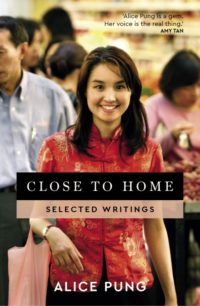

Close to Home: Selected Writings

Alice Pung

Black Inc.

Alice Pung’s new collection of essays and stories explore topics as diverse as migration; multiculturism and racism in modern Australia; the intergenerational trauma brought about by war; Buddhist meditation practices and 3 am Kmart shopping benders.

This collection of 40 of Alice Pung’s essays and stories, written over almost two decades, traces both her development as a writer and the changing landscape of Australian approaches to migration and multiculturalism from the 1980s to the present.

The writings are predominantly short, pithy non-fiction essays written in the first person. Despite Pung’s many experiences travelling and living overseas, most of the writings are set in Australia and explore aspects of Australian life. They cover a diverse range of topics, including the sense of belonging and identity in migrant families and communities; post-war trauma; the flavours, smells and colours of everyday life in Melbourne’s inner western suburbs; cross-cultural approaches to child-birth and post-partum recovery and support, and the things people buy on 3 am Kmart shopping expeditions.

Pung’s voice throughout the pieces is raw, honest, and often humourous and warm. She demonstrates that she is equally comfortable providing serious, critical reflections on politically charged topics as she is writing quirky, funny, light-hearted pieces. Several essays reflect on Pung’s experiences growing up in a migrant family in Australia in the 1980’s and 1990’s – eras influenced by policies of multiculturalism and assimilation polices respectively. Some reflect on the progressive, accepting approach to multiculturalism and diversity Pung experienced during primary school in the 1980’s; others recount and identify past and current Australian policies and laws engendering racism and intolerance and Pung and her family’s personal experiences of racism in both private and public domains.

Other essays explore Pung’s families’ experiences dealing with the intergenerational trauma brought about by war, her father being a survivor and refugee of the genocide in Cambodia under the Pol Pot regime and her mother having lived through the aftermath of the fall of Saigon. They explore the complex legacy of the severe trauma brought about by war, which can include strength, vitality and a profound sense of gratitude for the small pleasures of life, as well as a relentless sense of fear and anxiety about the safety and stability of life rebuilt in the wake of war.

Some favourite moments from the humorous, light-hearted pieces include Pung’s memories of electronics salesman Tony Tran singing Karaoke at her father’s Retravision store in Footscray and the hats sported by her parents when she was a child: her mother’s favourite ‘SONY – the One and Only cap’ which came free with their television and her father’s Akubra hat. Pung recounts that when the rest of the family didn’t wear the Akubra hats he had bought them to make them look like “quality Australians” and “not stand out in a crowd”, he once wore three Akubra hats stacked on top of each other, rendering him “a walking advertisement for Paul Ho Gan”. Pung also paints such a vivid, visceral picture of experiences such as shopping at Footscray’s little Saigon market that the reader can almost smell the raw meat, hear the yelling of the hawkers, and see the array of brightly coloured fruits in the stalls and the sludge underfoot.

In an essay titled “Writing about my Father” (178), Pung reflects on writing about her father’s experiences both during and after the war in her award-winning book Her Father’s Daughter. She explains that she deliberately chose a structure for the narrative that would reflect the truth and complexity of her father’s story rather than follow the predictable formula of the migrant success story and that, in doing so, she wanted to counter the notion that the only migrant or refugee story worth telling is one that leads to worldly success and assimilation at the end. Pung poignantly reflects that “we are a nation of immigrants and yet we need to keep our complex and multifaceted true selves apart in order to be a part of this national narrative … our current mainstream discourse about ‘those who’ve come across the seas’ is polarising and unsophisticated.”

This fine collection of writings provides an antidote to the insufficiencies of such mainstream discourse, providing refreshing and balanced ideas on those areas of Australian political, cultural and social life which require a more nuanced and complex approach.