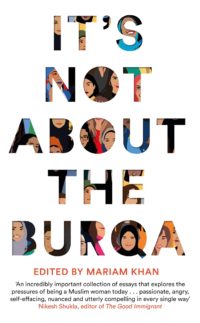

It’s Not About the Burqa

Ed. Mariam Khan

Pan Macmillan

The burqa has been the centrepiece of polarising debates surrounding Islamophobia in the last two decades. In Australia, Pauline Hanson shocked the nation in 2017 by entering the Senate donned in a black burqa in a call to make the garment illegal. In Britain, Boris Johnson was slammed last year for suggesting women wearing the burqa looked like “letter boxes” or “bank robbers.”

The burqa has been labelled a security risk or a signifier of Muslim women’s submissiveness in far-right debates across the Western world. And yet the voices given traction in these debates are very infrequently those of Muslim women themselves.

It’s Not About the Burqa, edited by British Islamic writer and activist Mariam Khan, features the stories of 20 women, all with vastly different experiences and relationships with their identity. We hear from journalists, lawyers, authors, women’s advocates, engineers, business women and unionists. The binding commonality is that they are all Muslim women who have made a life in the West, and they are all sick of politicians, the media or Eurocentric feminists speaking on behalf of them.

“We are not asking for permission anymore,” Mariam Khan resolves, “We are taking up space. We’ve listened to a lot of people talking about who Muslim women are without actually hearing Muslim women. So now, we are speaking. And now, it’s your turn to listen.”

The essays in this book cover many topics. There are stories exploring sexuality, marriage and divorce, the workplace, queerness, and the difficulties of growing up in a racist country balancing dichotomous identities. There are stories of intersectionality, between race, gender, sexual preference and faith. There are passionate frustrations over the misinterpretations that Muslim women face, and there is anger and pain. But these are also stories of joy and pride. Of strength and solidarity. And of hope.

Sufiya Ahmed, women’s rights activist and author of Secrets of the Henna Girl was brought up with the story of Khadija, the Mother of Believers and the Prophets first wife. Khadija was a successful businesswoman and the wealthiest merchant in Mecca, and taught Ahmed that “the foundations of my faith were fairness and justice, and that God does not promote gender inequality.”

“For those who have little knowledge of Islam,” Ahmed describes, “there is the assumption that Muslim women’s oppression stems from Islamic teachings. That is simply not the case.”

Saima Mir, a freelance journalist who faced judgement from her community after going through divorce, has a similar experience with her faith. “A woman who can read the Quran soon learns that her subjugation and oppression is a man made construct, very much against the law of Allah and his prophet.” The judgement she overcame was inflicted on her by society, not by any God.

“I am an emancipated Muslim woman” Mir writes proudly. “There is no contradiction in this.”

Amna Saleem, a Scottish Pakistani writer based in London, argues that though she doesn’t hate her community, it can do better, and change will not come from “mollycoddling Muslim men.”

“Muslim men will often insist we brush any wrongdoings…under the carpet for the sake of the Muslim community,” she writes, “and both the Muslim and the feminist in me is outraged when that happens.” She continues, “But I’m also not willing to see my community assaulted by a barrage of racism…Being a Muslim feminist too often means taking the blame for Muslim men’s weakness. We are stuck between two sets of people who try to use us as pawns, then get angry when we don’t oblige.”

Columnist and public speaker Mona Eltahaway describes this bind as being caught between a rock and a hard place. The rock, “an Islamophobic and racist right wing that is eager to demonise Muslim men, and to that end misuses our words with the way we resist misogyny within our own Muslim communities,” and a hard place, “Muslim communities that are eager to defend Muslim men, and…try to silence us and shut down the ways we resist misogyny.” Both sides are more focused upon each other than with Muslim women.

Nafisa Bakkar, another voice in It’s Not About the Burqa, created the online site Amaliah for Muslim women to have a space to exist on their own terms.

Though Muslim faces have become more common in the last few years, she believes in the importance of meaningful representation of Muslim women outside of corporate profit. There is a difference, she argues, between “seeing” Muslims and a real presence and visibility in the workplace, and between authentic Muslim women and palatable Muslim women.

“If we match up to agency briefs, if we fit into the existing set-up, then perhaps we can have equality – but an equality that feels increasingly superficial and lacking in authenticity.”

Yassmin Midhat Abdel-Magied, another voice in the book, understands only too well what it feels like to go outside of the “Model Minority” space allowed in the media. Abdel-Magied faced a public lynching from the press for speaking out on social media on Anzac Day.

Raifa Rafiq, a black Muslim British woman, argues that Muslim women living in the Western world are vulnerable in the public eye from the get go. They do not have the comfort of automatically belonging.

“Belonging is like a trampoline” she writes, “It is having the awareness that no matter how high you jump, how many risks you take, there is a place down there that that will absorb the force of your fall should you ever come crashing down.”

The essays in this book carve space for Muslim women to belong on their own terms – and make a crucial point. “If you want to make us feel included,” Afia Ahmed writes, “stop singling us out. If you truly believe it is not about the burqa, prove it and stop talking about it.”