During Senate estimates in October last year, the Australian government dug further into the deep and dark moral abyss in which it is stuck in relation to the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons.

In questioning by Tasmanian Labor Senator Lisa Singh, DFAT Assistant Secretary Richard Sadleir sought to explain the circumstances in which under Australia’s security doctrine the government regarded use of nuclear weapons as appropriate: “extended nuclear deterrence is something which comes to the fore in a situation of extreme emergency of the sort that has been referred to in terms of self-defence”. Senator Singh was appropriately appalled that there were any circumstances in which the government considered that use of nuclear weapons was appropriate.

Sadleir epitomised the fundamental Faustian bargain of nuclear deterrence – inextricably entwined as it is with a capacity and willingness to inflict indiscriminate radioactive incineration on millions of civilians, whether planned or by accident.

What credibility can Australia have in tut-tutting North Korea while it claims to need the option of US nuclear weapons being used on its behalf?

Shocking as this preparedness to be party to unleashing massive nuclear violence is, the government is being consistent. Consistent with what nuclear deterrence actually means; consistent with its refusal to support any statement that nuclear weapons must never be used again under any circumstances; consistent with its opposition to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (ban treaty), signed by 56 states since it opened for signature at the United Nations in New York on 20 September last year. Consistent with its claimed reliance on US nuclear weapons as fundamental to Australia’s national security and prosperity.

What is inconsistent is the Australian government’s hollow assurance that it is committed to achieving a world free of nuclear weapons, while claiming to need US nuclear weapons. This flagrant hypocrisy makes our nation an obstacle to disarmament and encourages proliferation. What credibility can Australia have in tut-tutting North Korea while it claims to need the option of US nuclear weapons being used on its behalf?

The 2017 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Melbourne-born International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which led the effort to establish a nuclear weapon ban treaty – an achievement the Norwegian Nobel Committee described as “groundbreaking”.

Yet the Australian Government has refused to join the ban treaty. In October last year, Mr Sadleir and DFAT senior legal advisor James Larsen, in Senate estimates for foreign minister Julie Bishop, gave reasoning for Australia’s prompt decision not to join the ban treaty, less than 3 weeks after it was adopted at the UN in New York.

These claims have wider relevance because they bear a striking similarity to arguments made by other nuclear-dependent and nuclear-armed governments.

Let’s take a look at what they said:

1. Australia doesn’t regard the ban treaty as an effective disarmament measure

All states agree that prohibition of nuclear weapons will be required at some point along the way towards achieving and maintaining a world free of nuclear weapons. But Australia argues that nuclear weapons should only be prohibited once they’ve been eliminated.

This flies in the face of logic, history and precedent. For every indiscriminate weapon which is in the process of being eliminated – biological and chemical weapons, anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions – codification of the norm of prohibition in a treaty has come first, providing the motivation and basis for progressive elimination of the weapon in question. More or less effectively, these treaties are working. They provide the proven path to disarmament: stigmatise, prohibit, eliminate. Australia has signed up to all of them; we played a leading role in the negotiation of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

The government is making an exception for the last and by far the most destructive WMD – nuclear weapons – because it continues to value them and believes US nuclear weapons might need to be used on behalf of Australia.

2. The ban treaty disregards the reality of the international security environment, highlighted by the grave threat posed by the DPRK

A few years ago, Iran would have been substituted for DPRK. Next year it might be another state. The DPRK is following the copybook laid out by every other nuclear-armed state and demonstrates that the means are available for any determined state to acquire nuclear weapons. The problem is weapons posing an existential threat to all humanity, not any particular set of fallible human hands controlling them.

No doubt, the international security environment is alarming. Relations between US/NATO and Russia are at their lowest ebb since the end of the Cold War, with military exercising and deployments becoming more provocative, existing nuclear weapons agreements like the INF (Intermediate Nuclear Forces) treaty in jeopardy, Russian annexation of Crimea, and no disarmament talks underway or planned. Tensions simmer between China, US, Japan and others in the South China Sea. Almost weekly border skirmishes, a continuing nuclear arms race, weak security of nuclear weapons, and policies envisioning early use of nuclear weapons highlight the real danger of armed conflict turning nuclear between India and Pakistan. The situation in various parts of the Middle East is hardly stable. Irresponsible explicit and increasingly extreme nuclear threats have escalated between DPRK and the US, bringing closer the grim prospect of war, including nuclear war. Nuclear threats have also been uttered in recent times by Prime Minister Theresa May, President Putin, and leaders in India and Pakistan.

Meanwhile no disarmament negotiations are underway or even being planned, all nuclear-armed states are committed to indefinite retention of their nuclear arsenals, and all are investing large sums – together over US$100 billion annually – in modernising them, making them more accurate and “usable”. It is no wonder that the 15 Nobel laureate and other custodians of the Doomsday Clock, along with most authoritative others, assess the dangers of nuclear war to be as high as they have ever been, and growing.

All this makes all the more urgent the need to reduce and remove the real danger of nuclear weapons being used. Progress proved possible during the icy depths of the Cold War – after the Cuban missile crisis, with the Partial Test Ban Treaty, with the START treaty, with reciprocating unilateral measures between the USSR and the US in the 1980s and early 90s. Increasing tensions and potential flashpoints, ongoing proliferation of nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them, dysfunctional leaders, increasing possibilities for cyberattack to trigger nuclear war are all reasons to intensify and not stall work to diminish nuclear dangers.

Explosion of US nuclear weapons in Australia’s name will cause indiscriminate nuclear violence just as surely as any others.

Setting conditions and moving goalposts, like trust and resolution of regional tensions, that are claimed to be required before disarmament can proceed, is an excuse to stall. We will never have a perfect world free of tensions, especially not in an era of accelerating climate disruption. This reality makes it all the more urgent to get nuclear weapons off the table. There will never be a better time to get on with nuclear disarmament than now.

There are nine national nuclear arsenals in the world, and the North Korean nuclear arsenal, of an estimated 10-20 assembled weapons, and having produced enough fissile material (nuclear bomb fuel) for between 30 and 60, is probably the only one not capable of triggering global cooling, which would cause billions of people around the world to starve. More than 90 per cent of the global nuclear arsenal is held by Russia and the US. These arsenals, and the arsenals of France, China, UK, Pakistan, India and Israel, pose a far greater risk to humanity.

If nuclear weapons are exploded, the effects will be the same no matter where they came from, whether they were used first or second or third. Explosion of US nuclear weapons in Australia’s name will cause indiscriminate nuclear violence just as surely as any others. As Ban Ki-moon said, there are no right hands for the wrong weapons.

Beatrice Fihn, Executive Director of ICAN, speaks at the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony. ICAN.

3. The treaty is fundamentally flawed and risks undermining the NPT

The claim that the ban treaty undermines the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) could hardly be further from the truth, and the government seems to have studiously avoided explaining its basis for this claim.

The ban treaty specifically refers to the NPT “as the cornerstone of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime”. Governments negotiating the ban treaty went to great lengths to reinforce the NPT, and every one of them has consistently expressed this support before, during and after the negotiations. They acted on the basis that Article 6 of the NPT obliges all governments to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures … relating to nuclear disarmament”.

Comprehensively prohibiting nuclear weapons as the ban treaty does is clearly “an effective measure”. Its provisions for the verified, irreversible elimination of nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons programs and facilities complement and build on the NPT and apply consistent standards to all states, essential to delivering disarmament and breaking the current “nuclear apartheid” logjam.

The ban treaty fills a legal gap, including in the NPT, which left nuclear weapons as the last and worst weapons of mass destruction not prohibited. It was way past due to fill this gap. A number of other multilateral treaties complement the NPT, all of them supported by Australia – the regional nuclear weapon free zone treaties, the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty – still not entered into force – among them. A fissile material treaty, supported by Australia, would add to them. Additional legal instruments will be needed to attain and maintain a world free of nuclear weapons, as is envisaged by the NPT.

4. The ban treaty undermines the nuclear safeguards system

Nuclear safeguards are (imperfect) measures applied by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to deter and provide early detection of diversion of nuclear material or technology to make nuclear weapons. The ban treaty does not undermine this system, and again the government avoids explaining their claim. The treaty clearly stipulates in Article 3 that joining states must maintain their safeguards obligations. If they do not yet have a Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (CSA) with the IAEA they must bring one into force. In both cases the treaty appropriately anticipates that states may adopt additional safeguards in the future.

Some of those who make this criticism point to the failure of the ban treaty to require a CSA and an Additional Protocol, with its more stringent provisions for inspection and monitoring of nuclear activities, to be the safeguards standard required of states which join the treaty. While this would arguably have been desirable, blaming the ban treaty for not strengthening the safeguards regime in a way that the NPT regime has failed to do over the past 20 years is seeking a scapegoat on a matter more properly within the province of the NPT. But the ban treaty does not allow any states joining to weaken their safeguards obligations, and is entirely consistent with every state eventually being required to apply the same safeguards standards.

For states that have, or have had, nuclear weapons when they sign the treaty, after the verified elimination of their nuclear weapons, facilities and programs, a high level of safeguards is required. Such states: “shall conclude a safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency sufficient to provide credible assurance of the non-diversion of declared nuclear material from peaceful nuclear activities and of the absence of undeclared nuclear material or activities in the State as a whole.” These requirements certainly cover the elements of the Additional Protocol, and this specification of what the safeguards need to accomplish in these circumstances is appropriate, as the safeguards system can be expected to and should evolve in line with technical and other developments.

5. The ban treaty will not eliminate a single nuclear weapon

This allegation is disingenuous and in bad faith. The ban treaty negotiations were open to all states. The nuclear-armed and nuclear-dependent states, with the exception of the Netherlands, chose to stay away. This was the first time ever that Australia has not joined a multilateral disarmament process. Hardly a sign of good faith.

States that don’t possess nuclear weapons obviously can’t eliminate them. However all people and all states are jeopardised by the existence of nuclear weapons, and all have a responsibility (including under the NPT) to achieve nuclear disarmament.

The main “practical steps” to non-proliferation and disarmament Australia includes in its self-titled “progressive” approach are entry into force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), a fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT), increased transparency about nuclear weapons holdings, work on verification issues, and meetings since 2010 of a dozen or so nations known as the Nuclear Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), which has achieved nothing significant. None of these would eliminate a single nuclear weapon either. To be sure, there is nothing wrong with any of these measures; however they have not been implemented in decades, and there are no foreseeable prospects they will be implemented.

Which states now assert their essential right and need to wield a smallpox or plague “deterrent”, or their legitimacy in threatening to use sarin nerve gas?

The ban treaty powerfully codifies in international law a rejection of the legitimacy of nuclear weapons in any hands. As we have seen with other weapons subject to prohibition, norms are powerful. Which states now assert their essential right and need to wield a smallpox or plague “deterrent”, or their legitimacy in threatening to use sarin nerve gas? The strength of the norm against chemical weapons led to the Syrian government being forced to join the Chemical Weapon Convention in 2013 and the destruction of 1300 tons of chemical weapons. Despite states like China, Russia and the US opposing the treaties banning landmines and cluster munitions, none of them any longer export these, manufacture and use have declined, and the US boasts its virtual compliance with the landmine ban even though it hasn’t joined that treaty.

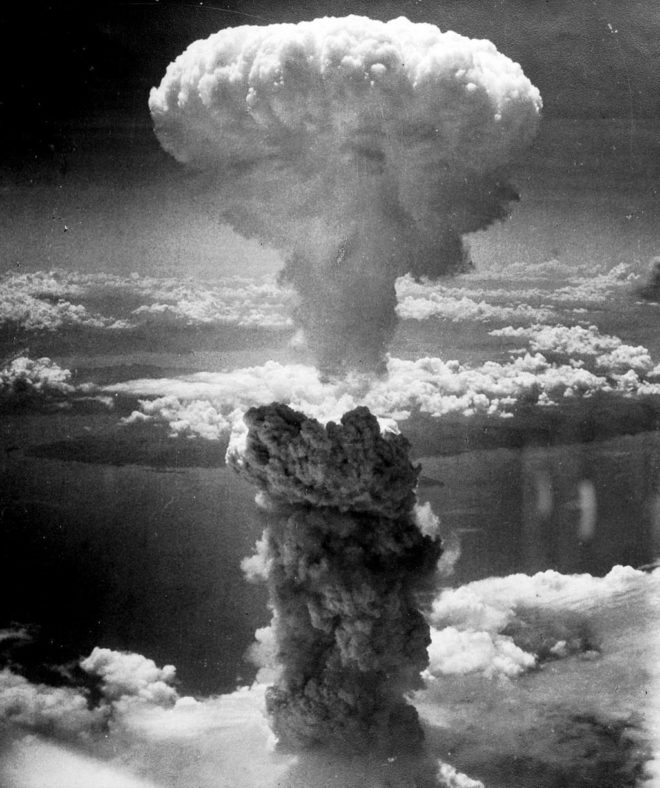

The mushroom cloud of the atomic bombing of the Japanese city of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Wikimedia

6. The ban treaty process abandoned the consensus-based framework

The ban treaty was negotiated in eight months because negotiations took place under the rules of the UN General Assembly, the most inclusive and fundamental organ of the UN, which in the absence of a consensus allows the votes of a two-thirds majority to decide matters of substance.

The requirement for consensus which applies to NPT meetings and to the UN Conference on Disarmament (CD) mean that these bodies can agree nothing if just one state objects. This means both bodies are reduced to lowest common denominator, and goes a considerable way to explaining why the NPT has been ineffective in advancing disarmament, and why the CD has not been able to agree even on an agenda for 21 years.

The claim that the ban treaty exacerbates divisions between states is spurious. The main sources of division are the existential threat posed by the nine states that claim a unique right to threaten indiscriminate globalized nuclear violence and their failure to deliver the disarmament they are obligated to. Differences that may be accentuated by intolerance and impatience with this moribund status quo are necessary and healthy to breaking the logjam in disarmament.

The standard by which any disarmament measure should be judged is twofold: does it progress the eradication of nuclear weapons and does it reduce the risks of nuclear war in the meantime?

The ban treaty provides pathways to join for states that are nuclear weapons free, have nuclear weapons currently, have owned them in the past, have nuclear weapons stationed on their territory, or like Australia assist in military preparations for their use.

Thus no state can legitimately claim that this treaty is not for them. It provides a moment of truth: if they are committed to disarmament they will sign; if they do not join, whatever they say, they are part of the problem rather than the solution. Sadly Australia still languishes on the wrong side of history.