Mohammad Ali Baqiri was only ten years old when he boarded the rickety boat headed for Australia. He remembers climbing aboard with his older brother, his parents remaining in Pakistan. He remembers travelling for seven days at sea, unsure of when they would reach Australian waters. He remembers being intercepted by the Australian Navy.

“The Navy told us to go back … there were people on the boat who had previously made the same journey and had been returned to Indonesia, those desperate passengers set the boat on fire. There were more than 100 people on board, including women and children. Everyone jumped in the water.”

It took two hours for the surviving asylum seekers to be plucked from the water that day. Two female asylum seekers drowned.

In 2014 the global number of refugees hit 50 million. The world has not seen mass migration this large since World War Two.

Despite such high numbers, the Australian government has closed off its borders to asylum seekers arriving by boat through the introduction of Operation Sovereign Borders.

Operation Sovereign Borders stipulates that all asylum seekers who arrive by boat to Australia must be held in offshore processing centres. If they are found to be genuine refugees, they will also be settled offshore.

The United Nations has reported that Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers breaches its human rights obligations under the UN Refugee Convention. The Australian public, however, largely support the policy.

Although Australia houses only 0.3 per cent of the world’s refugee population, Australians still believe we do too much. One poll showed 52 per cent of Australians think we take in too many refugees. The same study found 62 per cent of Australians called for the Abbott Government to “increase the severity of the treatment of asylum seekers.”

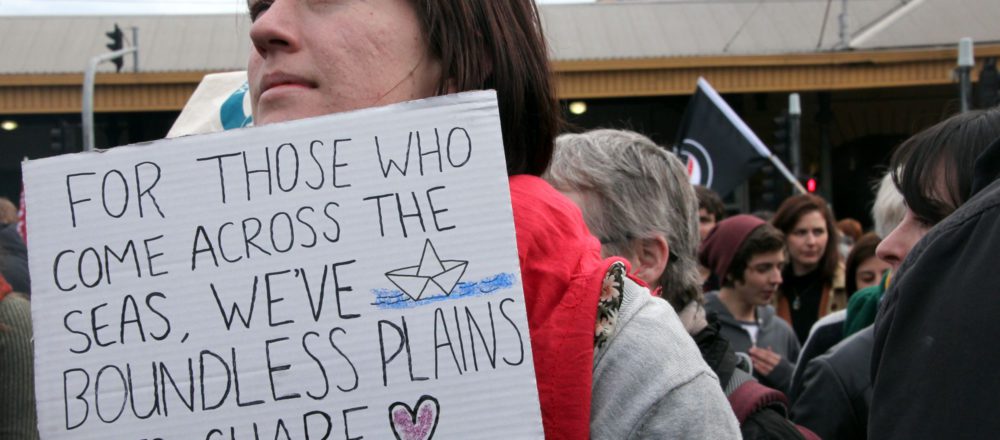

The second verse of Australia’s national anthem Advance Australia Fair, particularly the line “For those who’ve come across the seas, we’ve boundless plains to share” has truly been forgotten. But why are Australians are so unwilling to open their doors? One reason appears to be a perceived lack of integration by refugees in Australia, including a reluctance to work.

“There is a myth that people who come as refugees to Australia are just passive recipients of charity, that they don’t come to Australia to contribute and that they are a drain on resources,” explains Lucy Morgan, Information and Policy Coordinator for The Refugee Council of Australia.

Many Australians perceive people who come here to seek asylum as being reluctant to integrate into Australian society, and therefore a potential threat to the “Aussie” way of life. There are a number of Facebook groups sprouting up in support of sustaining “Australian culture”. One group, ‘Take Back Australia,” has almost 50,000 likes. The group describes itself as “Pro-Australian and pro-preservation of our way of life.”

The group’s administrator, who declined to disclose their name, said “We at this page, like most Australians only wish our legal immigrants assimilate like the immigrants of the past.” This sentiment runs true throughout the page, with one follower writing, “These NEW arrivals do not want to integrate, these persons are here to take over … Bloody wake up!!!”

Mohammad would also like Australia to wake up. The now 26-year-old Law and Management student at Victoria University is an avid campaigner for refugee rights.

“If we don’t praise our multiculturalism we’re not going to get anywhere,” he says.

Mohammad knows about getting somewhere. After three years spent in Nauru, Mohammad was granted a Temporary Protection Visa to live in Australia.

Mohammad settled in Dandenong, before moving to Shepparton in search of work for his older brother who was struggling after being denied access to English classes. Mohammad went to school, focused on learning English and eventually became the school captain at McGuire College in Shepparton. His brother now owns a farm employing local workers.

Mohammad’s story is not unique. A report from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre found asylum seekers are more likely to start their own businesses than the general Australian population.

“If you’ve taken the risk of having to flee your country and you’ve lost everything, the risk of starting a small business may not seem quite so scary,” Morgan explains.

Another man who did just that is John Gulzari. A Hazara from Afghanistan, John arrived in Australia by boat in 1999. After gaining his citizenship in 2007, John started his own real estate business.

“One of the reasons I was pushing to run my own company was to prove that I was not an economic migrant,” John says.

While the business did not thrive, John did. John became the first Hazara refugee candidate for the Victorian state election. John believes asylum seekers want to integrate into their communities. He considers integration as caring for, and contributing to, the country that he says saved his life. It’s not about drinking a beer and watching the footy.

John celebrates Australia day with pride, volunteers with the Country Fire Authority and participates in Anzac marches for the fallen soldiers who gave their lives so he could be safe in this country.

“We march every year because of how privileged, how lucky we are living here without any war or fear of killing,” he says.

Lucy Morgan says unlike other migrants, refugees do not have the option of returning home and therefore tend to fully commit to their new country.

“Once they are given the opportunity to restart their lives, they often grab that opportunity with both hands,” she says.

But opportunities are not always easily found.

In 2014, the Abbott Government introduced the Temporary Humanitarian Concern (THC) Visa. THC visas restrict visa holders from receiving English classes, sponsoring families and applying for any other permanent visas.

“The issue that we see with temporary protection visas is that the visa denies people the support to settle,” Morgan says.

They are potentially denied the support they need to make the successful transition from their highly traumatic refugee experience to rebuilding their lives in Australia.”

While all boat arrivals are currently being processed and settled offshore, there was a push within the Labour party to address their policy on asylum seeker treatment at a national conference in July. The conference addressed the need to ensure that asylum seekers will not be punished based on their mode of arrival, reducing detention to a measure of last resort. Katy Gallagher, the new senator for the ACT, told Fairfax she is “uncomfortable with what is going on now.”

News of a push within a major Australian party is good news for asylum seekers like John Gulzari. While he has had the opportunity to call Australia home, many others do not.

“We consider Australia our home, we are here shoulder to shoulder with other Aussies whether it is defending the country or making a good image for this country.”

—

Nicolle White is a freelance journalist with an interest in refugee policy. She runs “Refugee Stories“, an Instagram-based project promoting understanding of situations that lead to seeking refuge. You can find more of her work at www.nicollewhite.com.

Feature Image: Takver/Flickr