This article is part of our February theme, which focuses on one of the great silences in the human rights conversation in Australia: Prisoners’ Rights. Read our Editorial for more on this theme.

In March 2012 it will be twenty-one years since the release of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The report found that while Aboriginal deaths in custody did not happen at a higher rate than non-Aboriginal deaths in custody, the rate of imprisonment was many times higher. Western Australia’s Indigenous incarceration rate remains the highest in the country, where an Indigenous person is 23 times more likely to be imprisoned than a non-Indigenous person. Any consideration of overcrowding in prisons in Western Australia needs to be considered in this context.

Given the vast size of Western Australia (30 per cent of the Australian continent) many people from remote communities are jailed thousands of kilometres from home. In Acacia prison at any given time, there can be up to 200 Aboriginal people from remote communities incarcerated. The most common reasons for Indigenous prisoners to be in prison are driving offences, drinking offences, and non-payment of fines. The Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services in his unreleased, yet widely circulated draft report A Thematic Review of Overcrowding in Prisons (November 2009) identified the most overcrowded prisons in Western Australia as those where Indigenous prisoners are more likely to be held. During the course of my current PhD research I have heard from ex-prisoners and ex-staff that Aboriginal prisoners at Casuarina prison are usually housed in the oldest, most dilapidated part of the prisons, rather than the newer, better equipped sections.

WA’s tough on crime approach leads to overcrowded prisons

The latest Productivity Commission Report has a large section on incarceration, including a state-by-state breakdown. It is based on 2010 figures that show Western Australian prisons to be 30 per cent over capacity. By January 5 2012 this had risen to a prison population 50 per cent over capacity. Since 2007 the Western Australian prison population has increased sharply. This rise coincided with a change of state government in September 2008 when the Carpenter-led Labor government lost power to the Barnett-led Liberal government, which implemented an increasingly “tough on crime” approach to justice. This includes a tough approach to parole, leading to it not being granted as often, along with a decreased use of community service orders as an alternative. Statistics on these issues are available from the Corrective Services website.

Double bunking is the key cause of overcrowding and is now the norm in WA prisons. The Custodial Inspector’s reports of individual prisons contain photographs of instances of double bunking. Double bunking is the term used when extra mattresses or beds are put in place in cells; for example a cell designed for one person may have an extra mattress on the floor.

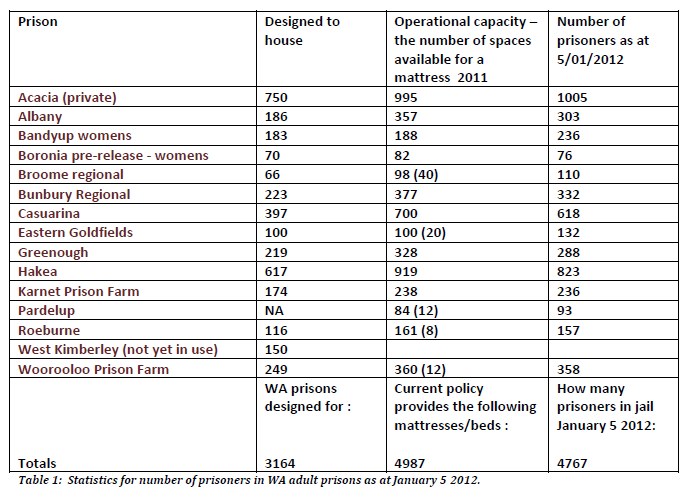

The following table gives a snapshot of the actual numbers in WA prisons as of the beginning of January 2012, based on information available at the Corrective Services website. As you can see, prisons in Western Australia are 50 per cent over “design capacity” across the board. However, the state government continues to refer to “operational capacity” as the base line and defends double bunking. You can follow the numbers of prisoners in WA prisons at the Department of Corrective Services website. “Design capacity” refers to the number of prisoners a prison was designed to house. This is how groups such as the Prison Officers Union and Deaths in Custody Watch Committee determine overcrowding levels. “Operational capacity” is the term the government uses as a baseline to determine overcrowding, and refers to the number of mattresses there are to put people on; these may or may not be actual bunks and includes mattresses on cell floors.

Overcrowding potentially costs lives. Despite the call of the Royal Commission almost twenty-one years ago to remove prisoner access to potential hanging points, deaths can still occur this way in Western Australian prisons. As evidenced by the Custodial Inspector’s reports, hanging points remain in some Western Australian prisons including Roeburne and Greenough. Further, where prisons are overcrowded it is not possible to renovate cells to meet safety standards. Overcrowding can also lead to important programs being compromised. For example, in Bunbury prison, the Custodial Inspector notes that the pre-release unit has had to be used for minimum security which has had a negative impact on the functioning of the pre-release unit.

Impact on vulnerable prisoners

The problem of overcrowding is exacerbated by the fact that those most at risk of being imprisoned are amongst the most vulnerable in our community. The Western Australia Supreme Court’s Equality Before the Law Benchbook gives an overview of imprisonment and mental illness. In 2005, the former Attorney General advised that prisoners were five to seven times more likely to have a mental illness than other people, and that in some prisons 25 per cent of the population had mental health illness and about half required hospitalisation in a forensic mental facility.

Overcrowding also make it impossible for rehabilitation work to be done effectively. Access to programs is limited and I have heard stories of people being denied parole as they have not completed the programs stipulated for them at sentencing. This is due to the inability to access programs, not because of a lack of the person in prison wanting to do the course.

Risks to prisoners and staff

The British Colombia Civil Liberties Association notes that double bunking can pose a threat to the privacy, health and safety of inmates and is, by definition, overcrowding as it is used in situations where more inmates are housed than a prison is designed to hold. Prisons require more than mattresses to be effective.

In his reports, the Custodial Inspector comments time and again that offices, classrooms, kitchens, dining areas, visitor areas, and exercise areas are not being expanded in Western Australian prisons to match the new prisoner numbers. The Prison Officers Union in Western Australia is concerned that this situation creates risks associated with control, and therefore staff and prisoner safety; risks to decency in the treatment of prisoners; and risks to the community when prisons cannot fulfil their rehabilitative role. So concerned are they that they have an ongoing Respect the Risk Campaign addressing just these issues.

Despite these concerns being raised in all of the Inspector’s reports on WA prisons in recent years, the overcrowding continues. In his most recent report on Bunbury prison (December 2011) he notes that the increase in violence in the prison can be directly attributed to overcrowding.

Government and NGO response

The independent reviewer of prisons in Western Australia, the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services was so concerned about overcrowding that, in 2009, he completed a Thematic Review into Overcrowding in WA Prisons. As mentioned above, the report was never endorsed by the Minister for release, though it is often quoted and copies have circulated relatively widely in Perth. Its contents are damning and refer to “the physical conditions in some of these prisons comparing poorly with those in many prisons across South-East Asia”. The report also noted that the taxpayer cost for keeping a person in prison for a year is around $100,000.

To address prison overcrowding the Deaths in Custody Watch Committee advocate for a Justice Reinvestment approach to crime. Justice reinvestment advocates for money usually spent on building and running prisons to be redirected towards advancing financially-sound, data driven criminal justice policies to break the cycle of recidivism, stop spiralling prison expenditures and make communities safer. It has been recommended in a number of recent reports, including those by Tom Calma, the Western Australian Parliament’s Community Development and Justice Standing Committee (rejected by the present government, though supported by opposition parties), the Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, and the Standing Committee on Environment and Public Affairs. To find out more about Justice Reinvestment you can follow the work of the Deaths in Custody Watch Committee in WA at www.deathsincustody.org.au

Justice Reinvestment has four clear steps:

Step 1: Identify the communities from which people in prison often originate and return.

Step 2: Work with the community to identify options to generate savings Provide policymakers with options to generate savings and increase public safety.

Step 3: Quantify savings and reinvest in identified communities.

Step 4: Measure and evaluate the impact on the identified community.

These four steps have been implemented in some states of the USA, and have quickly led to financial savings and either a levelling of incarceration rates or a drop in incarceration rates. Both the Greens and Labor parties have endorsed Justice Reinvestment as a good policy for Western Australia. What is happening in Western Australia is not sustainable. Given the increasing levels of overcrowding in Western Australian prisons and the associated costs these four steps make sense and are worthy of adoption and trial.

Rose Carnes (B.Ed, BSW(Hons)) is member of the Deaths in Custody Watch Committee in Western Australia, and is a PhD candidate at Murdoch University researching Indigenous prisoner education in Western Australian prisons. She has previously worked in teaching, counselling, crisis response, politics, management, domestic violence and community development in Tasmania and Western Australia.